Odds and Ends

- My hobbies

- Fiber!

- Wall of Daikon

- All my websites

- Desert

- Please Hear What I'm Not Saying by Charles C. Finn

- The Untold Want by Whitman

My hobbies

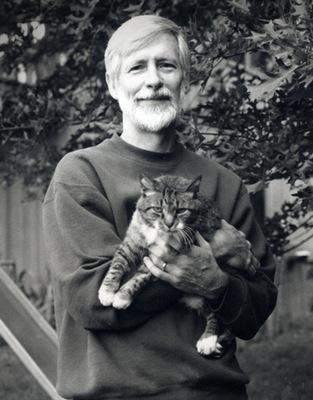

I've always had a main hobby or "special interest," which switches to a new one serially, a sort of one-at-a-time obsession which never really fades away:

- Telescopes

- Science fiction

- Radios

- Nero Wolfe novels

- Old Time radio

- Computers and mild hacking

- Electronics

- Ham radio

- History of science

- Playing guitar

- Running

- Reading poetry (never got any good at it, though)

- Mountain biking

- Large format photography, including color film/print developing

- Web and database programming (see link above, mostly .asp in VBScript)

- Running a web server

- ATV

- Camping in the desert

- Sony minidisc

- Collecting/organizing digital media

- Nature audio recording

- Timelapse video

- Exercise

- Midcentury modern architecture

- Nature drawing (failed)

- Driving/modding my FR-S

- Baseball (left over from when I was a kid, this didn't work out at all; too much information to process when the ball came toward me so I never had much hitting coordination, and then the MLB got greedier than I wanted to pay for so I stopped even watching)

- History of alchemy

- Sumo fan (thanks, NHK!)

Once I've had it, I always have it. Except exercise. I've let that one go a bit. And of course baseball.

Fiber!

All my servers appeared down the last couple days. I got Utopia fiber into the house after a ten-year wait, and they set me up on a private IP address, which meant that no ports got through to my servers. Servers have ports on which they listen for incoming requests, and mine heard nothing. I just got switched to a different VLAN which assigns an external IP address, so I can now see the ports. It's a dynamic IP, but I'm already set up for that, so the domain name (kf7k.com) switches to the new IP in a minute when it changes. Nice. Fiber is fast, but there are some slow connection setup times.

Wall of Daikon

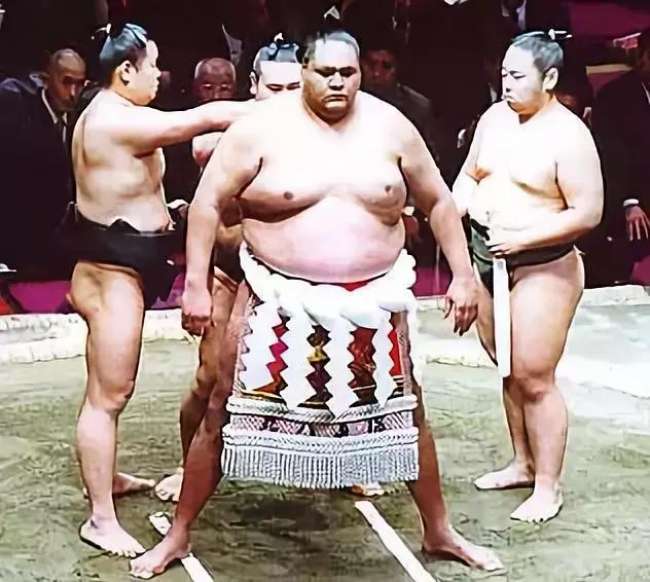

Okay, I'll say it here: I'm a fan of sumo wrestling.

It started back in the '90's when Akebono, an enormous Hawaiian guy, rose the the highest rank of Yokazuna, the first non-Japanese wrestler ever to do so. He was so popular that American sports broadcasters included some sumo coverage on certain weekends. It was fun, exciting, and novel. Then when Akebono retired, 2001, sumo disappeared from TV.

But then, digital over-the-air TV brought an unique thing: subchannels. The way it works is that when a major broadcaster takes a digital spot, there is more bandwidth there than they need, so they can put other channels in the space left. These other channels are usually lower resolution, and which do not have a large market. The Utah Education Network, channel 9.1, has four subchannels, 9.4 is the NHK TV English service. NHK is the Japanese National Network. Every two months, NHK includes coverage of the latest Sumo Basho (tournament), and this is where I rediscovered Sumo.

Sumo is Japans biggest sport. Big enough to close the shops when it's on TV.

I've found that the NHK app also shows these broadcasts on demand, and they are streamed at better resolution than the TV does. So grab the app if you want to enjoy the spectacle. It can be fun. NHK dos the occasional weekend live coverage, where you see all the ritual, but it's the highlight show each day I enjoy the most.

Beware there are many terms in Japanese that won't exactly make sense until you learn what they are. I'll add a selected list below, one I got from Wikipedia.

Here are some media, other than NHK:

News:

Podcasts:

- Grand Sumo Breakdown

- Tachiai

YouTube channels:

- Chris Sumo

- Kintamayama

- Japanese Sumo Association (Official channel)

- NHK World Japan

Scroll down for the ending, below the dictionary

Sumo Terminology, from Wikipedia:

B

Banzuke for the January 2012 tournament

Banzuke for the January 2012 tournament

- banzuke (番付)

- List of sumo wrestlers according to rank for a particular grand tournament, reflecting changes in rank due to the results of the previous tournament. It is written out in a particular calligraphy (see sumō-ji) and usually released on the Monday 13 days prior to the first day of the tournament.

- basho (場所)

- 'Venue'. Any sumo tournament. Compare honbasho.

- binzuke (鬢付け)

- Also called binzuke abura ('binzuke oil'). A Japanese pomade, which consists mainly of wax and hardened chamomile oil that is used to style sumo wrestlers' hair and give it its distinctive smell and sheen. It is used exclusively by tokoyama hairdressers.

C

- chankonabe (ちゃんこ鍋)

- A stew commonly eaten in large quantities by sumo wrestlers as part of a weight gain diet. It contains dashi or stock with sake or mirin to add flavor. The bulk of chankonabe is made up of large quantities of protein sources, usually chicken, fish (fried and made into balls), tofu, or sometimes beef; and vegetables (daikon, bok choy, etc.).

- chikara-mizu (力水)

- Power-water. The ladleful of water with which a wrestler will ceremonially rinse out his mouth prior to a bout. It must be handed to him by a wrestler not tainted with a loss on that day, so it is either handed to him by the victorious wrestler of the previous bout if he was on the same side of the dohyō, or if that wrestler was defeated, by the wrestler who will fight in the bout following. This system works well until the last match of the day (musubi no ichiban (結びの一番)) when one side will not have someone to give them the power water. This is due to the fact that one of the sides from the previous match lost and there is no next match, so there is neither a winner from the previous match, nor a next wrestler to give them the water. In this case a winner from two or three prior matches will be the one to give them the power water. This wrestler is known as the kachi-nokori (勝ち残り), which means "the winner who remains".

- chikara-gami (力紙)

- Power-paper. The piece of calligraphy-grade paper with which a wrestler will ceremonially wipe the sweat off his face prior to a bout. It must be handed to him by a wrestler not tainted with a loss on that day, in the same manner of the chikara-mizu (力水) described above.

- chirichōzu (塵手水)

- 'Washing the hands'. One of the many rituals preceding a sumo bout, in which both wrestlers squat facing each other, display their open hands, clap and extend their arms. This is done to demonstrate they do not hold or carry weapons, and that the fight will be a fair and clean one.

- chonmage (丁髷)

- Traditional Japanese haircut with a topknot, now largely only worn by rikishi and so an easy way to recognize that a man is in the sumo profession.

D

- danpatsu-shiki (断髪式)

- Retirement ceremony, held for a top wrestler in the Ryōgoku Kokugikan some months after retirement, in which his chonmage, or top knot, is cut off. A wrestler must have fought as a sekitori in at least 30 tournaments to qualify for a ceremony at the Kokugikan.

- dohyō (土俵)

- The ring in which the sumo wrestlers hold their matches, made of a specific clay and spread with sand. A new dohyō is built prior to each tournament.

- dohyō-iri (土俵入り)

- Ring-entering ceremony, performed only by the wrestlers in the jūryō and makuuchi divisions. The east and west sides perform their dohyō-iri together, in succession; the yokozuna have their own individual dohyō-iri performed separately. The main styles of yokozuna dohyō-iri are Unryū and Shiranui, named after Unryū Kyūkichi and Shiranui Kōemon. A yokozuna performs the ceremony with two attendants, the tachimochi (太刀持ち) or sword carrier, and the tsuyuharai (露払い) or dew sweeper.

E

- ebanzuke (絵番付)

- Picture banzuke with paintings of top division sekitori, gyōji and sometimes yobidashi.

F

- fundoshi (褌)

- Also pronounced mitsu. General term referring to a loincloth, ornamental apron, or mawashi.

- fusenpai (不戦敗)

- A loss by default for not appearing at a scheduled bout. If a wrestler withdraws from the tournament (injury or retirement), one loss by default will be recorded against him on the following day, and simple absence for the remainder. Recorded with a black square.

- fusenshō (不戦勝)

- A win by default because of the absence of the opponent. The system was established for the honbasho in the May 1927 tournament. After the issue of Hitachiiwa Eitarō, the system was modified to the modern form. Prior to this, an absence would simply be recorded for both wrestlers, regardless of which one had failed to show. Recorded with a white square.

G

- gumbai

- A war fan, usually made of wood, used by the gyōji to signal his instructions and final decision during a bout. Historically, it was used by samurai officers in Japan to communicate commands to their soldiers.

- ginō-shō (技能賞)

- Technique prize. One of three special prizes awarded to rikishi for performance in a basho.

- gyōji (行司)

- A sumo referee.

H

- hakkeyoi (はっけよい)

- The phrase shouted by a sumo referee during a bout, specifically when the action has stalled and the wrestlers have reached a stand-off. It means, "Put some spirit into it!"

- henka (変化)

- A sidestep to avoid an attack. If done, it is usually at the tachi-ai to set up a slap-down technique, but this is often regarded as bad sumo and unworthy of higher ranked wrestlers. Some say it is a legitimate "outsmarting" move, and provides a necessary balance to direct force, henka meaning "change; variation".[4]

- heya (部屋)

- Literally "room", but usually rendered as "stable". The establishment where a wrestler trains, and also lives while he is in the lower divisions. It is pronounced beya in compounds, such as in the name of the stable. (For example, the heya named Sadogatake is called Sadogatake-beya.)

- higi (非技)

- 'Non-technique'. A winning situation where the victorious wrestler did not initiate a kimarite. The Japan Sumo Association recognizes five higi. See kimarite for descriptions.

- honbasho (本場所)

- A professional sumo tournament, held six times a year since 1958, where the results affect the wrestlers' rankings.

- hyōshi-gi (拍子木)

- The wooden sticks that are clapped by the yobidashi to draw the spectator's attention.

I

- ichimon (一門)

- A group of related heya. There are five groups: Dewanoumi, Nishonoseki, Takasago, Tokitsukaze, and Isegahama. These groups tend to cooperate closely on inter-stable training and the occasional transfer of personnel. All ichimon have at least one representative on the Sumo Association board of directors. In the past, ichimon were more established cooperative entities and until 1965, wrestlers from the same ichimon did not fight each other in tournament competition.

- itamiwake (痛み分け)

- A draw due to injury. A rematch (torinaoshi) has been called but one wrestler is too injured to continue; this is no longer in use and the injured wrestler forfeits instead.[1] The last itamiwake was recorded in 1999.[7] Recorded with a white triangle.

J

- jōi-jin (上位陣)

- "High rankers". A term loosely used to describe wrestlers who would expect to face a yokozuna during a tournament. In practice this normally means anyone ranked maegashira 4 or above.

- jonidan (序二段)

- The second-lowest division of sumo wrestlers, below sandanme and above jonokuchi.

- jonokuchi (序の口)

- An expression meaning "this is only the beginning". The lowest division of sumo wrestlers.

- jūryō (十両)

- "Ten ryō", for the original salary of a professional sumo wrestler. The second-highest division of sumo wrestlers, below makuuchi and above makushita, and the lowest division where the wrestlers receive a salary and full privileges.

K

- kachi-koshi (勝ち越し)

- More wins than losses for a wrestler in a tournament. This is eight wins for a sekitori with fifteen bouts in a tournament, and four wins for lower-ranked wrestlers with seven bouts in a tournament. Gaining kachi-koshi generally results in promotion. The opposite is make-koshi.

- kachi-nokori (勝ち残り)

- Literally translates as "the winner who remains". During a day of sumo the "power water" is only given to the next wrestler by either a previous winner on their side of the ring or the next wrestler to fight on their side of the ring so as not to receive the water from either the opposite side or from a loser, which would be bad luck. However at the end of the day, one side will not have a winner or a next wrestler to give them the water. In this case the wrestler who was the last to win from their side will remain at the ringside in order to give them the "power water". This individual is known as the kachi-nokori.

- kadoban (角番)

- An ōzeki who has suffered make-koshi in his previous tournament and so will be demoted if he fails to score at least eight wins. The present rules date from July 1969 and there have been over 100 cases of kadoban ōzeki since that time.

- kantō-shō (敢闘賞)

- Fighting Spirit prize. One of three special prizes awarded to rikishi for performance in a basho.

- kenshō-kin (懸賞金)

- Prize money based on sponsorship of the bout, awarded to the winner upon the gyōji's gunbai. The banners of the sponsors are paraded around the dohyō prior to the bout, and their names are announced. Roughly half the sponsorship prize money goes directly to the winner, the remainder (minus an administrative fee) is held by the Japan Sumo Association until his retirement.

- keshō-mawashi (化粧廻し)

- The loincloth fronted with a heavily decorated apron worn by sekitori wrestlers for the dohyō-iri. These are very expensive, and are usually paid for by the wrestler's organization of supporters or a commercial sponsor.

- kimarite (決まり手)

- Winning techniques in a sumo bout, announced by the referee on declaring the winner. The Japan Sumo Association recognizes eighty-two different kimarite.

- kinboshi (金星)

- "Gold star". Awarded to a maegashira who defeats a yokozuna during a honbasho. It represents a permanent salary bonus.

- kinjite (禁じ手)

- "Forbidden hand". A foul move during a bout, which results in disqualification. Examples include punching, kicking and eye-poking. The only kinjite likely to be seen these days (usually inadvertently) is hair-pulling.

- Kokusai Sumō Renmei (国際相撲連盟)

- International Sumo Federation, the IOC-recognized governing body for international and amateur sumo competitions.

- komusubi (小結)

- "Little knot". The fourth-highest rank of sumo wrestlers, and the lowest san'yaku rank.

- kore yori san'yaku (これより三役)

- "These three bouts". The final three torikumi during senshūraku. The winner of the first bout wins a pair of arrows. The winner of the penultimate bout wins the string. The ultimate bout winner is awarded the bow.[8]

- kuroboshi (黒星)

- "Black star". A loss in a sumo bout, recorded with a black circle.

- kyūjō (休場)

- A wrestler's absence from a honbasho, usually due to injury.

M

- maegashira (前頭)

- "Those ahead". The fifth-highest rank of sumo wrestlers, and the lowest makuuchi rank. This rank makes up the bulk of the makuuchi division, comprising around 30 wrestlers depending on the number in san'yaku. Only the top ranks (maegashira jō'i (前頭上位)) normally fight against san'yaku wrestlers. Also sometimes referred to as hiramaku (平幕), particularly when used in contrast to san'yaku.

- make-koshi (負け越し)

- More losses than wins for a wrestler in a tournament. Make-koshi generally results in demotion, although there are special rules on demotion for ōzeki. The opposite is kachi-koshi.

- makushita (幕下)

- "Below the curtain". The third highest division of sumo wrestlers, below jūryō and above sandanme. Originally the division right below makuuchi, explaining its name, before jūryō was split off from it to become the new second highest division.

- makuuchi (幕内) or maku-no-uchi (幕の内)

- "Inside the curtain". The top division in sumo. It is named for the curtained-off waiting area once reserved for professional wrestlers during basho, and comprises 42 wrestlers.

- man'in onrei (満員御礼)

- Full house. Banners are unfurled from the ceiling when this is achieved during honbasho. However, it is not necessary to be at 100% capacity to unfurl the banner. Typically when seats are over 80% filled the banner is unfurled, however they have been unfurled with numbers as low as 75% and not unfurled with numbers as high as 95%.

- matta (待った)

- False start. When the wrestlers do not have mutual consent in the start of the match and one of the wrestlers starts before the other wrestler is ready, a matta is called, and the match is restarted. Typically the wrestler who is at fault for the false start (often this is both of them; one for giving the impression that he was ready to the other and the other for moving before his opponent was ready) will bow to the judges in apology. The first kanji means 'to wait', indicating that the match must wait until both wrestlers are ready.

- mawashi (廻し)

- The thick-waisted loincloth worn for sumo training and competition. Mawashi worn by sekitori wrestlers are white cotton for training and colored silk for competition; lower ranks wear dark cotton for both training and competition.

- mizu-iri (水入り)

- Water break. When a match goes on for around 4 minutes, the gyōji will stop the match for a water break for the safety of the wrestlers. In the two sekitori divisions, he will then place them back in exactly the same position to resume the match, while lower division bouts are restarted from the tachi-ai.

- mochikyūkin (持ち給金)

- A system of bonus payments to sekitori wrestlers.

- mono-ii (物言い)

- The discussion held by the shimpan when the gyōji's decision for a bout is called into question. Technically, the term refers to the querying of the decision: the resulting discussion is a kyogi. Literally means, a "talk about things".

N

- negishi-ryū (根岸流)

- The conservative style of calligraphy used in the banzuke. See sumō-ji.

- Nihon Sumō Kyōkai (日本相撲協会)

- The Japan Sumo Association, the governing body for professional sumo.

- nokotta (残った)

- Something the referee shouts during the bout indicating to the wrestler on defense that he is still in the ring. Literally translates as "remaining" as in remaining in the ring.

O

- ōichōmage (大銀杏髷)

- Literally "ginkgo-leaf top-knot". This is the hair style worn in tournaments by jūryō and makuuchi wrestlers. It is so named because the top-knot is fanned out on top of the head in a shape resembling a ginkgo leaf. It is only worn during formal events such as tournaments. Otherwise even top rankers will wear their hair in a chonmage style.

- oyakata (親方)

- A sumo coach, almost always the owner of one of the 105 name licenses (toshiyori kabu). Also used as a suffix as a personal honorific.

- ōzeki (大関)

- "Great barrier", but usually translated as "champion". The second-highest rank of sumo wrestlers.

R

- rikishi (力士)

- Literally, "powerful man". The most common term for a professional sumo wrestler, although sumōtori is sometimes used instead.

S

Sumōmoji sample depicting the term edomoji

Sumōmoji sample depicting the term edomoji

- sagari (下がり)

- The strings inserted into the front of the mawashi for competition. The sagari of sekitori wrestlers are stiffened with a seaweed-based glue.

- sandanme (三段目)

- "Third level". The third lowest division of sumo wrestlers, above jonidan and below makushita.

- sanshō (三賞)

- "Three prizes". Special prizes awarded to makuuchi wrestlers for exceptional performance.

- san'yaku (三役)

- "Three ranks". The "titleholder" ranks at the top of sumo. There are actually four ranks in san'yaku: yokozuna, ōzeki, sekiwake and komusubi, since the yokozuna is historically an ōzeki with a license to perform his own ring-entering ceremony. The word is occasionally used to refer only to sekiwake and komusubi.

- san'yaku soroibumi (三役揃い踏み)

- Ritual preceding the kore yori san'yaku or final three bouts on the final day (senshūraku) of a honbasho, where the six scheduled wrestlers, three from east side and three from the west side in turn perform shiko simultaneously on the dohyō.

- sekitori (関取)

- Literally "taken the barrier". Sumo wrestlers ranked jūryō or higher.

- sekiwake (関脇)

- The third-highest rank of sumo wrestlers.

- senshūraku (千秋楽)

- The final day of a sumo tournament. Senshūraku literally translates as "many years of comfort." There are two possible explanations for the origins of this term. In gagaku (traditional Japanese court music) the term is tied with celebratory meaning to the last song of the day. In classic nōgaku theater there is a play known as Takasago, in which the term is used in a song at the end of the play. Today the term is used in kabuki and other types of performances as well.

- shikiri (仕切り)

- "Toeing the mark". The preparation period before a bout, during which the wrestlers stare each other down, crouch repeatedly, perform the ritual salt-throwing, and other tactics to try to gain a psychological advantage.[12]

- shikiri-sen (仕切り線)

- The two short white parallel lines in the middle of the ring that wrestlers must crouch behind before starting a bout. Introduced in the spring tournament of 1928, they are 90 cm (35 in) long, 6 cm (2.4 in) wide and placed 70 cm (28 in) apart using enamel paint.[13]

- shiko (四股)

- The sumo exercise where each leg in succession is lifted as high and as straight as possible, and then brought down to stomp on the ground with considerable force. In training this may be repeated hundreds of times in a row. Shiko is also performed ritually to drive away demons before each bout and as part of the yokozuna dohyō-iri.

- shikona (四股名)

- A wrestler's "fighting or ring name", often a poetic expression which may contain elements specific to the wrestler's heya. Japanese wrestlers frequently do not adopt a shikona until they reach makushita or jūryō; foreign wrestlers adopt one on entering the sport. On rare occasions, a wrestler may fight under his original family name for his entire career, such as former ōzeki Dejima and former yokozuna Wajima.

- shimpan (審判)

- Ringside judges or umpires who may issue final rulings on any disputed decision. There are five shimpan for each bout, drawn from senior members of the Nihon Sumō Kyōkai, and wearing traditional formal kimono.

- shini-tai (死に体)

- "Dead body". A wrestler who was not technically the first to touch outside the ring but is nonetheless ruled the loser due to his opponent having put him in an irrecoverable position.[14]

- shiomaki (塩撒き)

- One of the many rituals preceding a sumo bout, in which the wrestlers throw handfuls of salt before entering the dohyō. According to Shinto beliefs, salt possesses purifying properties; as they cast salt into the ring, the wrestlers would then be cleansing the dohyō of bad energy and possibly protecting themselves from injury. The average amount a wrestler grabs and throws is around 200 g (7.1 oz), although some wrestlers throw up to 500 g (18 oz).[16]

- shokkiri (初っ切り)

- A comedic sumo performance, a type of match common to exhibition matches and tours, similar in concept to the basketball games of the Harlem Globetrotters; often used to demonstrate examples of illegal moves.

- shukun-shō (殊勲賞)

- Outstanding performance prize. One of three special prizes awarded to rikishi for performance in a basho.

- sumō-ji (相撲字)

- Calligraphy style with very wide brushstrokes used to write the banzuke.

- sumōtori (相撲取)

- Literally, "one who does sumo". Sumo wrestler, but occasionally refers only to sekitori.

T

- tachi-ai (立ち合い)

- The initial charge at the beginning of a bout.

- tawara (俵)

- Bales of rice straw. Tawara are half-buried in the clay of the dohyō to mark its boundaries.

- tegata (手形)

- "Hand print". A memento consisting of a wrestler's handprint in red or black ink and his shikona written by the wrestler in calligraphy on a square paperboard. It can be an original or a copy. A copy of a tegata may also be imprinted onto other memorabilia such as porcelain dishes. Only sekitori wrestlers are allowed to make hand prints.

- tegatana (手刀)

- "Knife hand". After winning a match and accepting the prize money, the wrestler makes a ceremonial hand movement with a tegatana known as tegatana o kiru (手刀を切る) where he makes three cutting motions in the order of left, right, and center.

Y

- yobidashi (呼出 or 呼び出し)

- Usher or announcer. General assistants at tournaments. They call the wrestlers to the dohyō before their bouts, build the dohyō prior to a tournament and maintain it between bouts, display the advertising banners before sponsored bouts, maintain the supply of ceremonial salt and chikara-mizu, and any other needed odd jobs.

- yokozuna (横綱)

- "Horizontal rope". The top rank in sumo, usually translated "Grand Champion". The name comes from the rope a yokozuna wears for the dohyō-iri. See tsuna.

- yumitori-shiki (弓取式)

- The bow-twirling ceremony performed at the end of each honbasho day by a designated wrestler, the yumitori, who is usually from the makushita division, and is usually a member of a yokozuna's stable.

- yūshō (優勝)

- A tournament championship in any division, awarded to the wrestler who wins the most bouts.

All this is one big lead-in to what I wanted to post today. One of my favorites is Shodai, an Ozeki (second-highest rank), who graduated from NODAI, the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Get it, Shodai from NODAI), and NODAI had a very unusual thing they do, the Daikon Dance. Daikons are large Japanese radishes, not spicy, that cook up really nicely. [On American farms they are sometimes used as a cover crop, as "oilseed radish."] Here is the Daikon Dance:

One American sumo commentator thought that Shodai looked something like a daikon, and Shodai has a nice defensive way of wrestling, so he refers to the "Wall of Daikon" when Shodai is unbeatable. Here is Shodai vs. Hoshoryu, Shodai is in the black mawashi (belt):

Wall of Daikon.

All my websites

I have a lot of websites. I'll list them here so I can remember them all. All links open in a new window.

https://radar.kf7k.com Live aircraft position reporting around my house

https://cloud.kf7k.com Private data cloud

https://photos.kf7k.com My photos

https://blog.kf7k.com This blog

https://weather.kf7k.com Weather from a station at my house

https://otr.kf7k.com My small collection of old time radio programs

https://www.kf7k.com/ My entry page, with links to a few more websites

Some sound recordings

Some time-lapse I made a while ago

Our wedding photos

Desert

The desert is a strange place to live. I call it desert, and then I know that most of you think sand dunes. There's a big difference between desert and dunes. Dunes are boring unless you ride an ATV or are a photographer. Sand. More sand. Sand in piles. Sand in waves. Sand in your shoes. Sand that won't hold your tent stakes. Sand that is home to a few bugs, an occasional whisp of grass, an itinerant population of recreators, and the Sherriff's portable jail trailer on Labor Day weekend.

Desert is different. There is life in the desert. Juniper and pinyon pines dot the landscape. I say dot, because that's what the aerial maps show. Billions of these small trees, but they are not densely packed into the landscape; there is just too much desert out there. Trees need to be spread thin. They don't get an easy start. Maybe there is a series of wet winters to help get the seeds growing. Saplings are rare, not just all the same age, so I doubt plentiful water is the missing factor. The trees in the desert don't block the view.

Fires are rare here too, the fire being unable to spread to any neighboring trees after a lightning strike. Solitary trees, loosely associated, like older suburban homes where you bought more land than the footprint of the building plus six feet on each side, a plot with a front yard and a back yard and a driveway on one side, and enough room for laundry lines on the other, room to breathe. The small trees grow in pairs or singly. Most are alone. They stand on a heap of their old needles. I call them needles because I don't have a better word for them. Juniper "leaves" aren't sharp like the pine needles are, but they form a similar heap at the base of the tree. Small mammals seem to like it there. So do scorpions. It's hard to imagine, when I look at one, that the heap was not there when the tree was young. What happened to the branches on the sapling that were low to the ground, are they still there under the heap, or did they fall away and become part of the heap? When the small blue berries, hard as rock, fall from the juniper, they roll down off the heaps and spread themselves. Self preservation, that's what the trees do.

It's hard not to think of the desert as a person. The skin of the desert is where we stand, but the canyons, the cliffs, speak to a hard life. The desert doesn't cover over its reality, the rock and the scars are always there to see. And you can see some of the damage we humans have done, but most isn't visible any more. Some soils are full of fungus and bacteria, feeding each other, scaley and black. That type of crust is easily killed; walk across it and your footprints stay for a decade. But eventually all traces of your passage are erased. The desert has no interest in preserving the past, and it has wind and rain to help it forget. It has a long life, a slow life, and the hastiness of a vacation can't really disturb it. Even the big dugways, ramps of earth that hug a hillside to gain access to the tops of the plateaus, even those behemoths are gone in 50 years. Made of dirt, they give way to running water. There isn't running water every year, mind, sometimes there is no running water in a decade. But a big storm will come and erase half the roadbed in ten minutes, sending it all down to the wash below. And this it becomes impassable, and without traffic packing the surface, making it resistant to more rain, the rest washes out in ten, twenty more years. Some ATV riders, the braver ones who can control their bikes well, or the dumb ones who have no idea that their bikes can roll, will try the washed-out dugway like a roller coaster ride, but they dig it up more than pack it down. Ten years? Five with a good storm or two?

Plants always survive the desert. They have patience. They are content to drop dozen, dozens, hundreds, thousands of seeds? year after year with no expectation that any of them will germinate. They feed the rodents. But occasionally one will germinate, and maybe even grow to maturity. Some years are fantastic for this. But it's not useful for plant life unless the previous year was one of the rare years when all the plants bloomed well. I've seen one of those years in the desert. It's a surprise if you know the landscape well, and expect to see a few blooms of penstemon, globemallow, and primrose, and one spring you arrive and the entire surface is colored with blooms you've never seen before, red, yellow, pink, mauve, purple, blue, plants you never noticed were there. Seeds in abundance, dropped all over, and some that aren't feeding the rodents and birds find a place to wait. They are patient, like the the rest of the desert.

Rock is patient. Desert rock isn't like the granite of the mountains or back East. It's soft. Sometimes, in what is called the Cutler formation northeast of Moab, it looks like it flows like mud. You'd think that rock was very soft. It isn't. Climbers pound pitons into it and it doesn't crack, it doesn't pull out. it's hard. But it has flowed in the past. it looks like mud. Time, I think, can do many things. Make rock flow like a semisolid seems to be one of them.

The rock is mostly red. Iron compounds that were freed from the basement rocks when there was oxygen in the air all turned red, then they settled into new rock formations. Sandstone formation, anyway. It will weather. The wind and the water will turn it back into sand. That's the time-scale of the desert. We are fleeting bacteria on its skin. It's dealing with rock pushing up from the basement of tome, and wearing down from the action of the wind. Wind destroys rock? If you give it time. It's an artistic process, producing arches, cavities, layers, exposing the flaws when the sediment was laid down, sometimes the waves on the sand when it was laid down. The desert tells you its real past, the long past. It doesn't tell you its immediate past, the time when trees were growing. It doesn't care about your footprints. Those go away in our own lifetimes. What cares the desert of a time as short as man?

The animals of the desert are aloof. Interested in our food, not in us, as it should be. We play in stories, drama, diversions, addictions, none of which have the least interest to a chipmunk. Let them raid the campsite after we are asleep. They have better things to do when we are awake. They have no interest in our world, while we look at theirs with longing. A simplicity of life. Not boring, lurking with large dangers like hawks and coyotes. They have families, but no drama, food but no work, live in a beautiful world they never need to clean. The bigger the animal, the bigger the mess.

Coyotes are messy. Carcasses they find, denude, leave behind for the bugs to finish. Coyotes have family life, too, and I suppose that can get messy. When they howl at night, the soprano howl and yip and whine, irresistible for the rest of the pack and they to join in. A celebration of family in the middle of the night. Wakes up the humans and makes them wonder. Coyotes feel closeness.

I've overlooked canyons, vast landscapes of sand and rock and juniper, smelling the cliffrose rise from the wash below and felt at home there. It wasn't home because the desert welcomed me there; it didn't care, probably didn't know I was there. It was home because I love the rock, and the sand, and the juniper. Petrified wood is my friend, and I recognize it every time it's there. The wind is my friend, and I welcome it. The sun, when the breeze is cold, is my friend and I turn my face to it. Sometimes the sun isn't my friend; it's the desert, but I live with it. Water is my friend. I hoard it. Water is a treasure in the desert. Rain is not my friend. I don't need water outside, I need it in my belly. Rain can turn the painted colors of the Chinle formation, leftovers of volcanic ash, into a mud so slippery you can't stand on it. What good does that do me?

The rock has a name. At least when it's one big rock it does. The tall red cliffs of the Wingate. The wind-carved layer of the Entrada. I've mentioned the mud-flow look of the Cutler. The white hillocks of the Navajo. The mudflat waves of the Moenkopi. Each has a character, the way it feels, the flatness of the rock, the way it sounds when you walk on it, the traction it gives underfoot, the color of it's eroded sand. Formations are like neighborhoods; some friendly, some not; some you get close to , touch, be intimate, some you can't approach.

You can see more photos here.

Please Hear What I'm Not Saying by Charles C. Finn

Please Hear What I'm Not Saying

Don't be fooled by me.

Don't be fooled by the face I wear

for I wear a mask, a thousand masks,

masks that I'm afraid to take off,

and none of them is me.

Pretending is an art that's second nature with me,

but don't be fooled,

for God's sake don't be fooled.

I give you the impression that I'm secure,

that all is sunny and unruffled with me, within as well as without,

that confidence is my name and coolness my game,

that the water's calm and I'm in command

and that I need no one,

but don't believe me.

My surface may seem smooth but my surface is my mask,

ever-varying and ever-concealing.

Beneath lies no complacence.

Beneath lies confusion, and fear, and aloneness.

But I hide this. I don't want anybody to know it.

I panic at the thought of my weakness exposed.

That's why I frantically create a mask to hide behind,

a nonchalant sophisticated facade,

to help me pretend,

to shield me from the glance that knows.

But such a glance is precisely my salvation, my only hope,

and I know it.

That is, if it's followed by acceptance,

if it's followed by love.

It's the only thing that can liberate me from myself,

from my own self-built prison walls,

from the barriers I so painstakingly erect.

It's the only thing that will assure me

of what I can't assure myself,

that I'm really worth something.

But I don't tell you this. I don't dare to, I'm afraid to.

I'm afraid your glance will not be followed by acceptance,

will not be followed by love.

I'm afraid you'll think less of me,

that you'll laugh, and your laugh would kill me.

I'm afraid that deep-down I'm nothing

and that you will see this and reject me.

So I play my game, my desperate pretending game,

with a facade of assurance without

and a trembling child within.

So begins the glittering but empty parade of masks,

and my life becomes a front.

I idly chatter to you in the suave tones of surface talk.

I tell you everything that's really nothing,

and nothing of what's everything,

of what's crying within me.

So when I'm going through my routine

do not be fooled by what I'm saying.

Please listen carefully and try to hear what I'm not saying,

what I'd like to be able to say,

what for survival I need to say,

but what I can't say.

I don't like hiding.

I don't like playing superficial phony games.

I want to stop playing them.

I want to be genuine and spontaneous and me

but you've got to help me.

You've got to hold out your hand

even when that's the last thing I seem to want.

Only you can wipe away from my eyes

the blank stare of the breathing dead.

Only you can call me into aliveness.

Each time you're kind, and gentle, and encouraging,

each time you try to understand because you really care,

my heart begins to grow wings--

very small wings,

very feeble wings,

but wings!

With your power to touch me into feeling

you can breathe life into me.

I want you to know that.

I want you to know how important you are to me,

how you can be a creator--an honest-to-God creator--

of the person that is me

if you choose to.

You alone can break down the wall behind which I tremble,

you alone can remove my mask,

you alone can release me from my shadow-world of panic,

from my lonely prison,

if you choose to.

Please choose to.

Do not pass me by.

It will not be easy for you.

A long conviction of worthlessness builds strong walls.

The nearer you approach to me the blinder I may strike back.

It's irrational, but despite what the books say about man

often I am irrational.

I fight against the very thing I cry out for.

But I am told that love is stronger than strong walls

and in this lies my hope.

Please try to beat down those walls

with firm hands but with gentle hands

for a child is very sensitive.

Who am I, you may wonder?

I am someone you know very well.

For I am every man you meet

and I am every woman you meet.

Charles C. Finn

September 1966

You can read a collection of stories about the poem's impact in Please Hear What I'm Not Saying: a Poem's Reach around the World

The Untold Want by Whitman

THE untold want, by life and land

ne’er granted,

Now, Voyager, sail thou forth,

to seek and find.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892). Leaves of Grass. 1900.