History of Alchemy

Prehistory to Newton

- Timeline of Alchemy

- 01 Pre-alchemy

- 02 Thales of Miletus: Egyptian Creation Myths?

- 03 Plato

- 04 Aristotle

- 05 Diogenes: Challenging Philosophy

- 06 Alexander: Spreading Ideas

- 07 Astrology and Magic: Status Quo

- 08 Democritus: What Might Have Been

- 09 Pseudo-Democritus

- 10 Translations from the Greek

- 11 Cleopatra and the Philosophers

- 12 The Earliest Chemistry

- 13 Visions of Alchemy

- 14 Gnosticism

- 15 Hermes Trismegistus

- 16 Stephanos of Alexandria

- 17 Can We Copy the Alchemists?

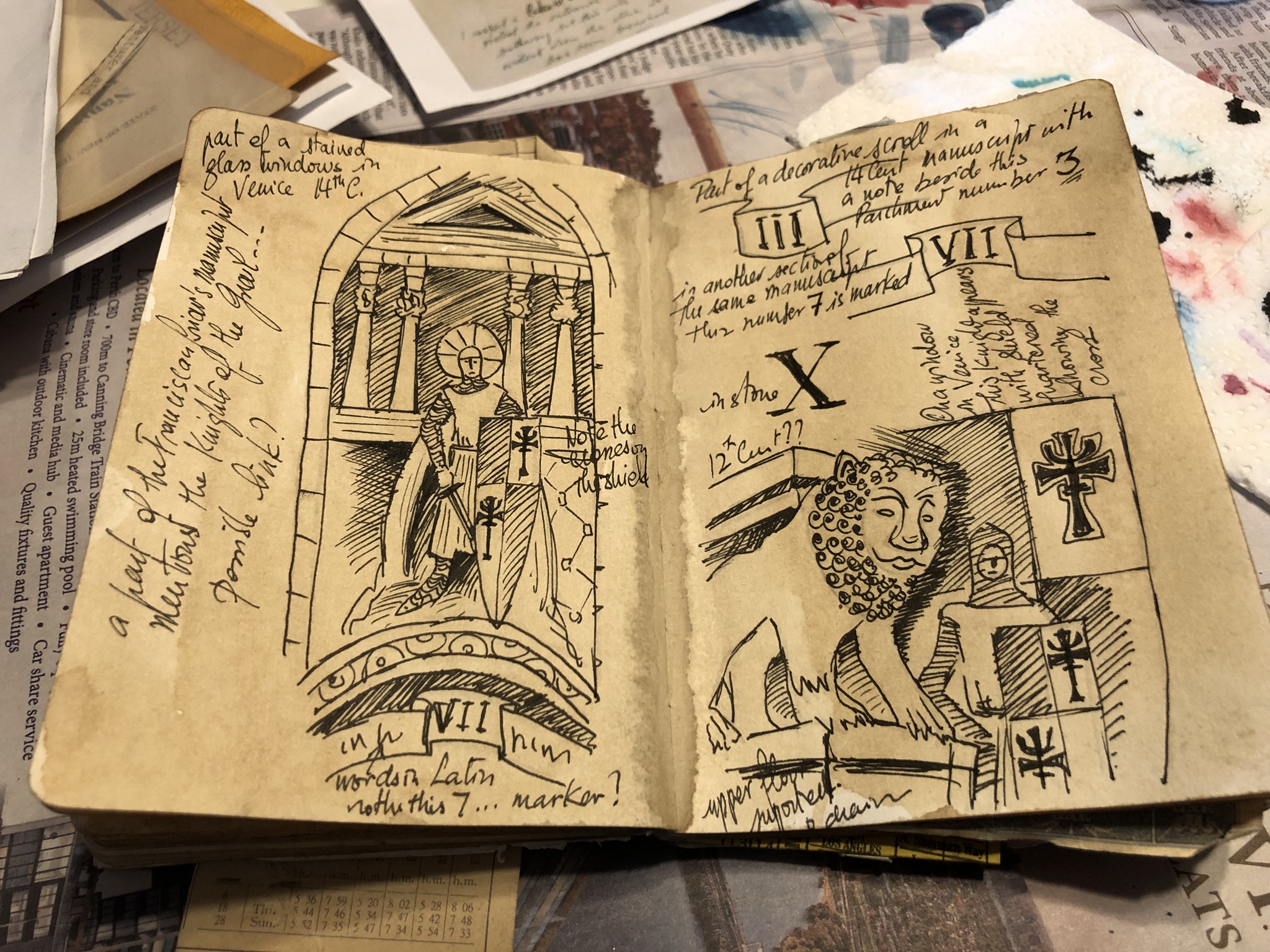

- 18 My Alchemy Journal

- 19 Roman Alchemy

- 20 Chinese Alchemy

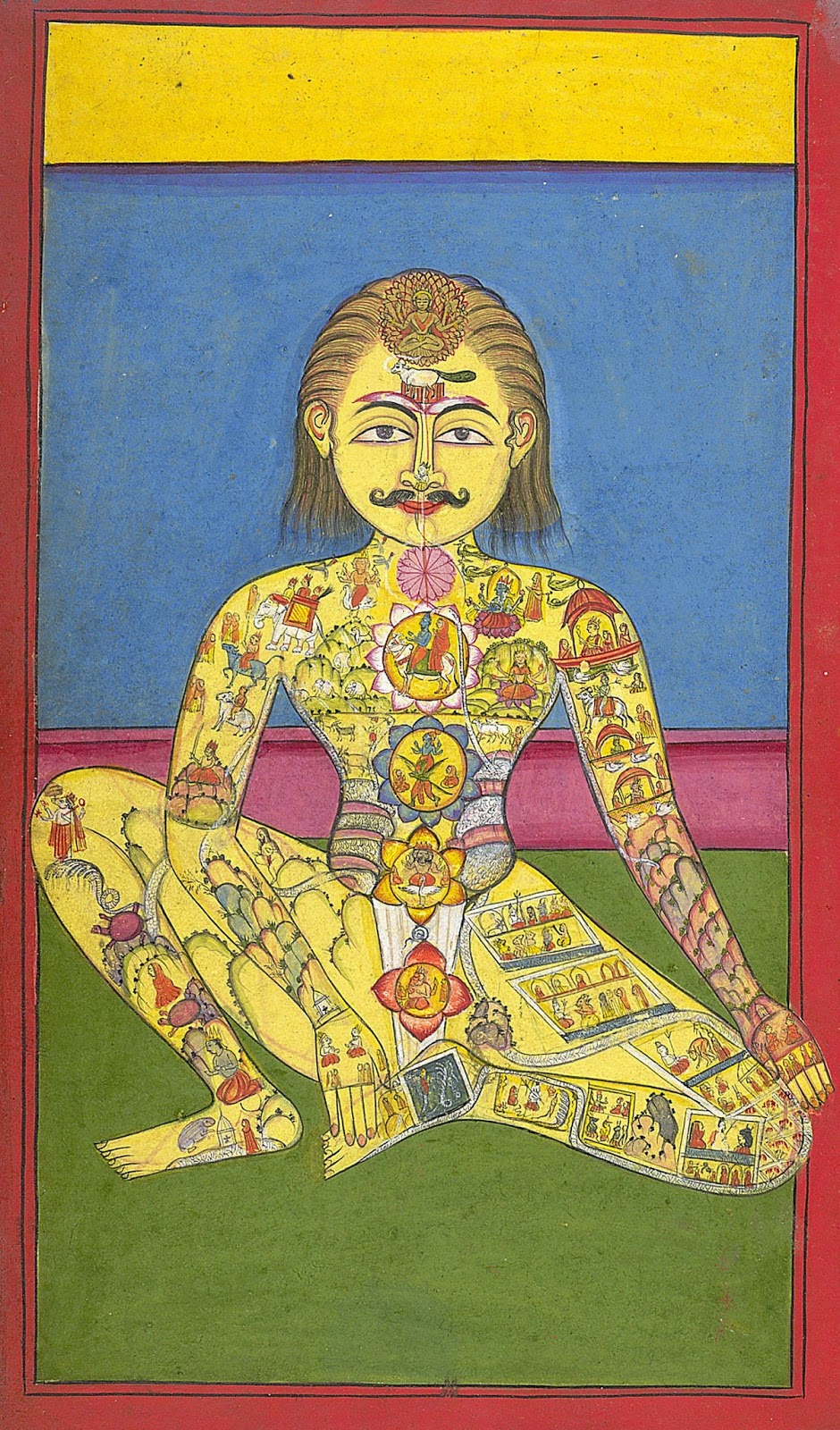

- 21 Indian Alchemy

- 22 Alchemy and Greek Medicine

- 23 ESOTERICA Another take on Alchemy

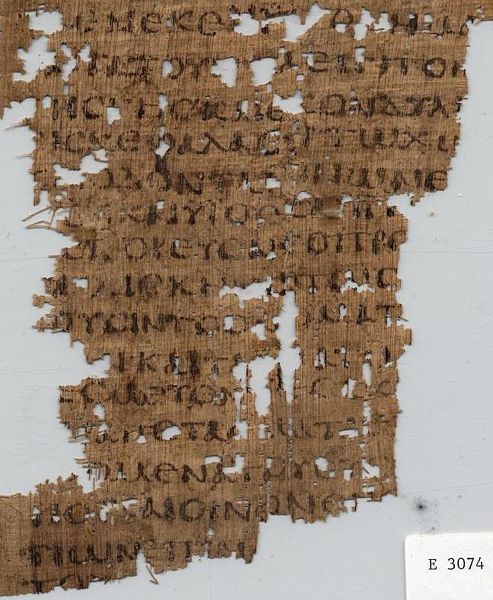

- 24 The Rise of Islam and Oxyrynchus

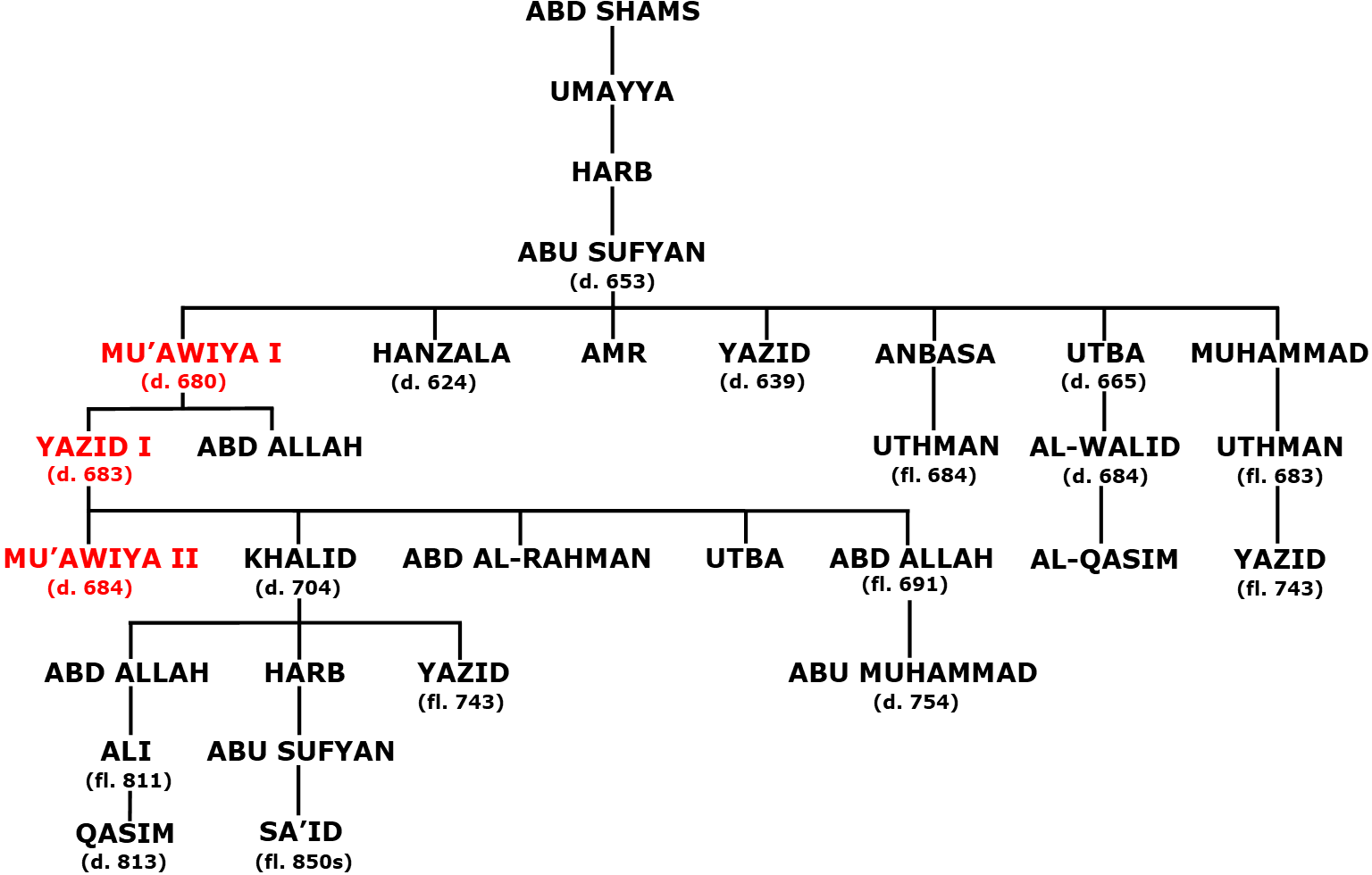

- 25 Khalid ibn Yazid

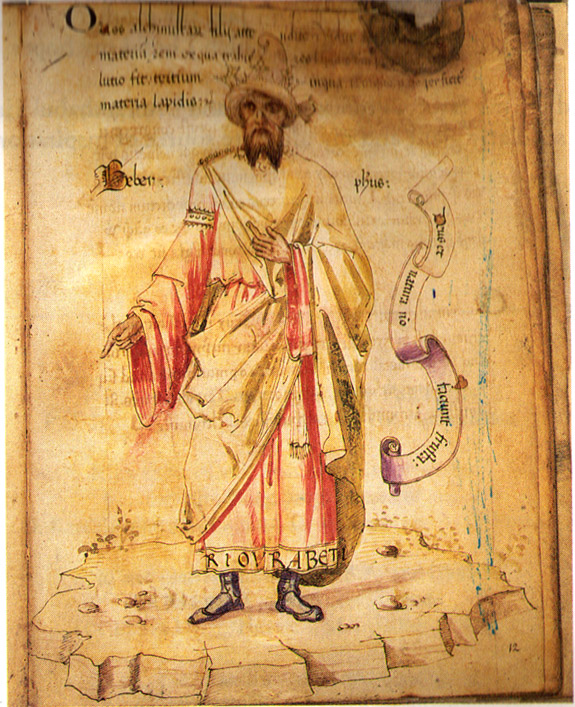

- 26 Jabir ibn Hayyan

- 27 What Jabir Said

- 28 ibn Umayl

- 29 al-Rāzī

- 30 ibn Sīnā (Avicenna)

- 31 Andalusian Spain and the Transfer of Philosophical Thought

- 31.2 Artephius

- 32 Albertus Magnus

- 33 Roger Bacon

- 34 Arnold of Villanova

- 35 Raymond Lull

- 36 Who was Geber?

- 37 Petrus Bonus

- 38 John Dastin and the Pope

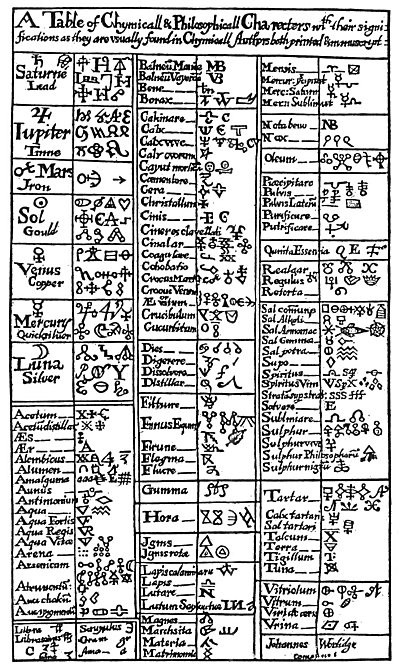

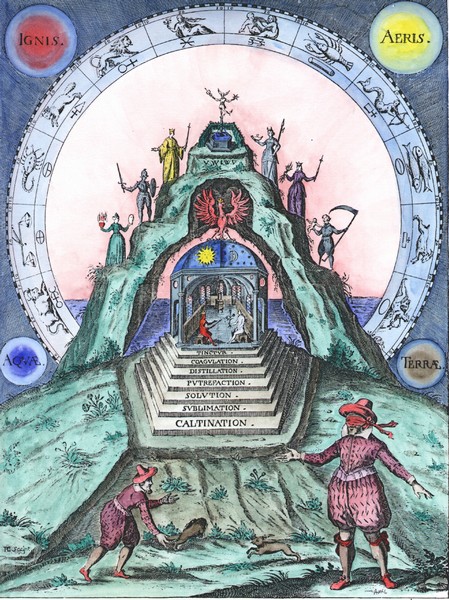

- 39 Alchemical Symbolism

- 40 Alchemical Cons

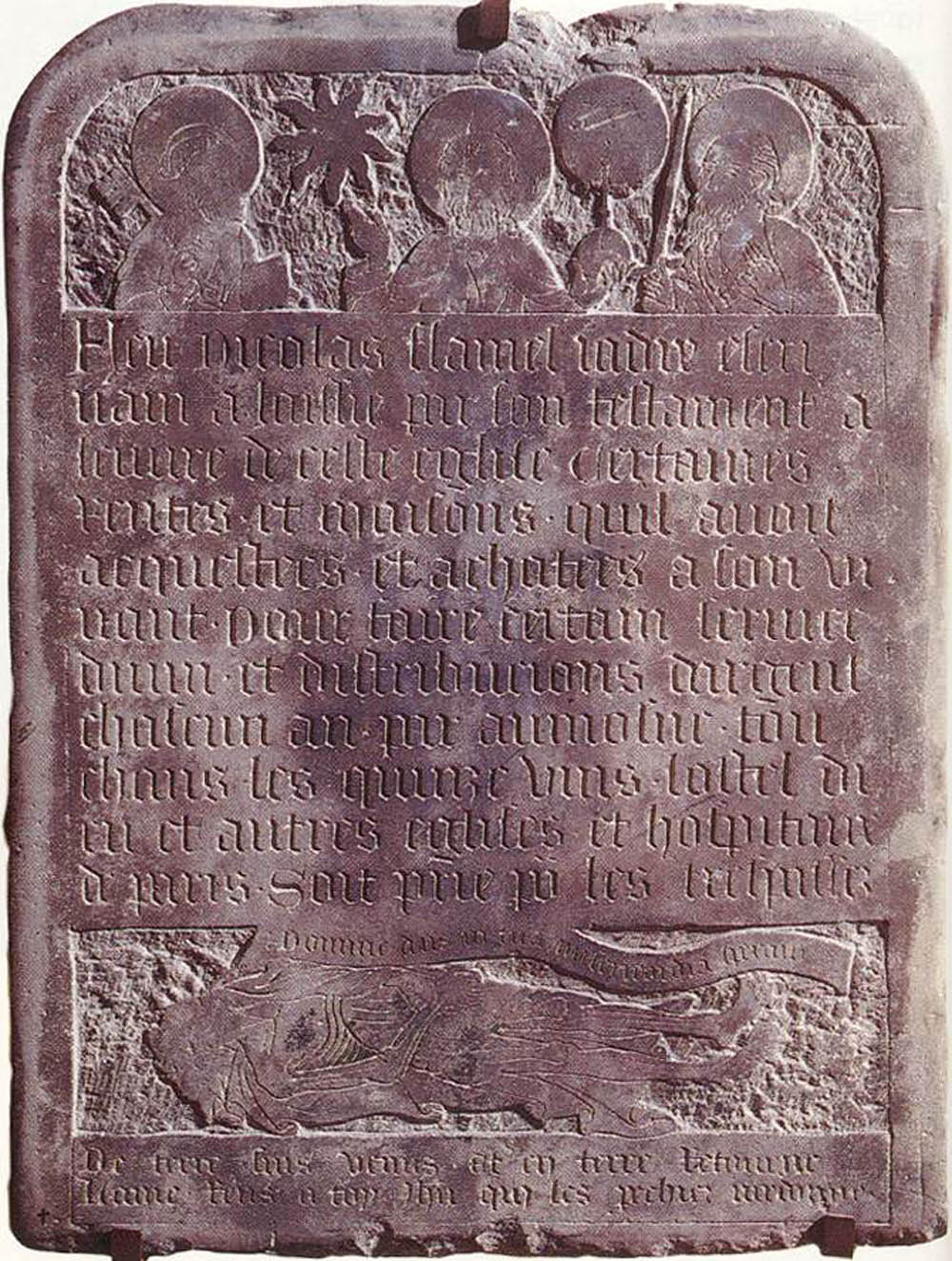

- 41 Nicolas Flamel

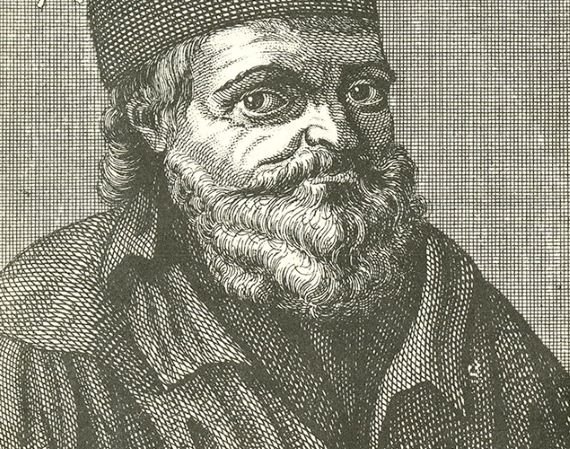

- 42 Bernard of Trevisan

- 43 George Ripley

- 44 The Fall of Constantinople

- 45 Paracelsus

- 46 Francis Anthony

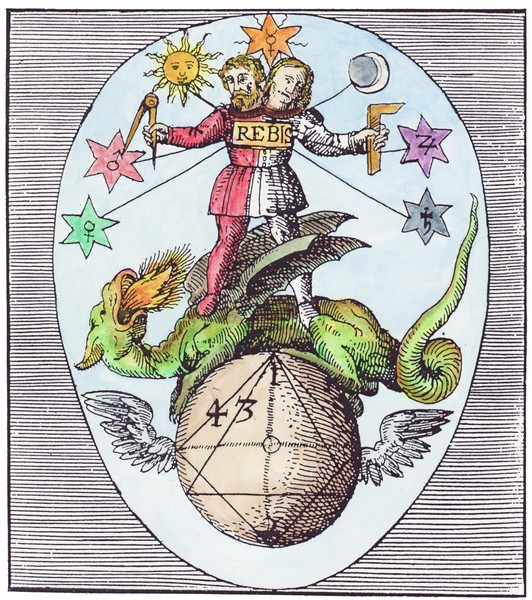

- 47 Michael Sendivogius

- 48 Petrus Ramus

- 49 The Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross

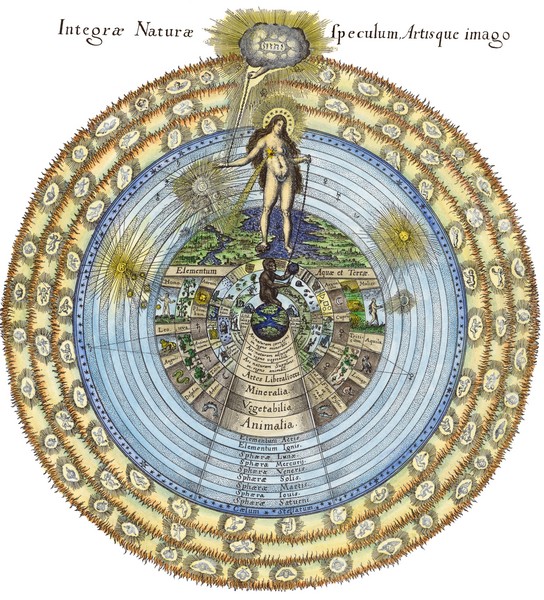

- 50 Robert Fludd

- 51 Gabriel Plattes

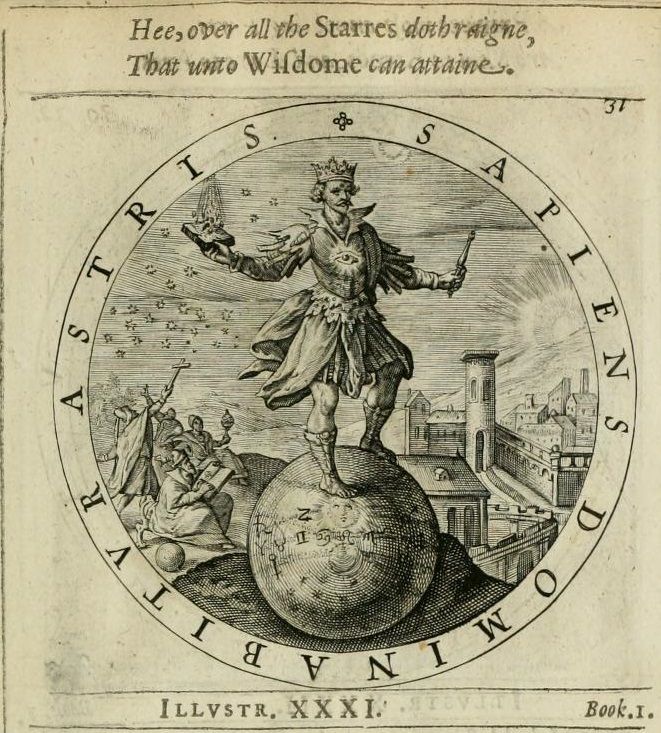

- 52 Emblem Books

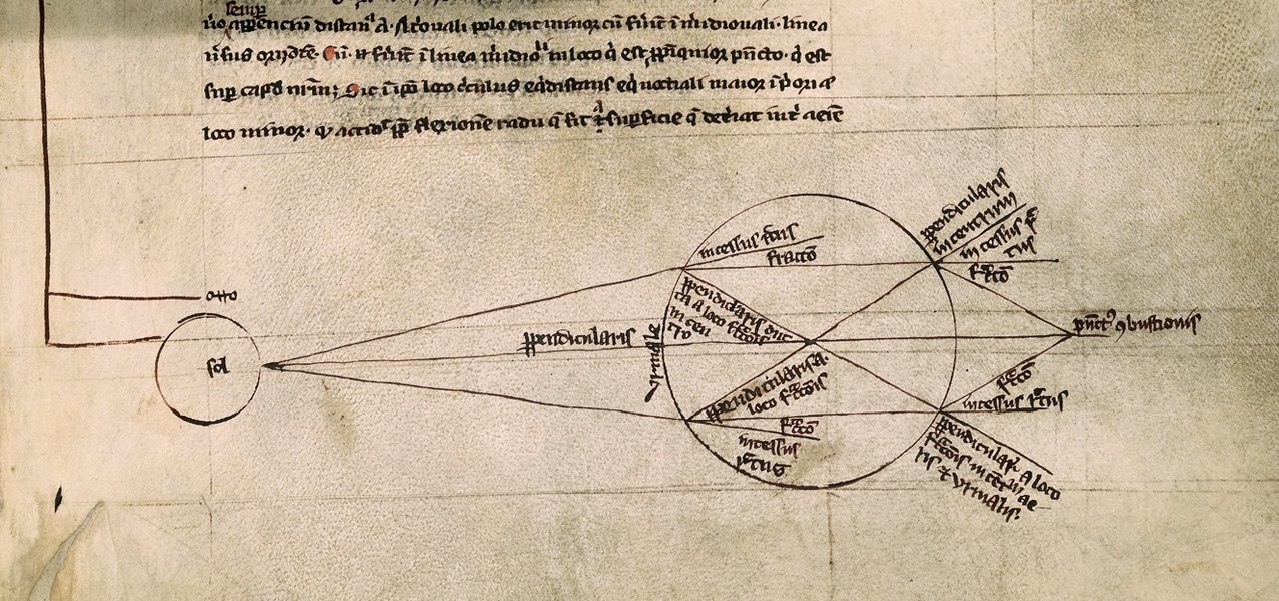

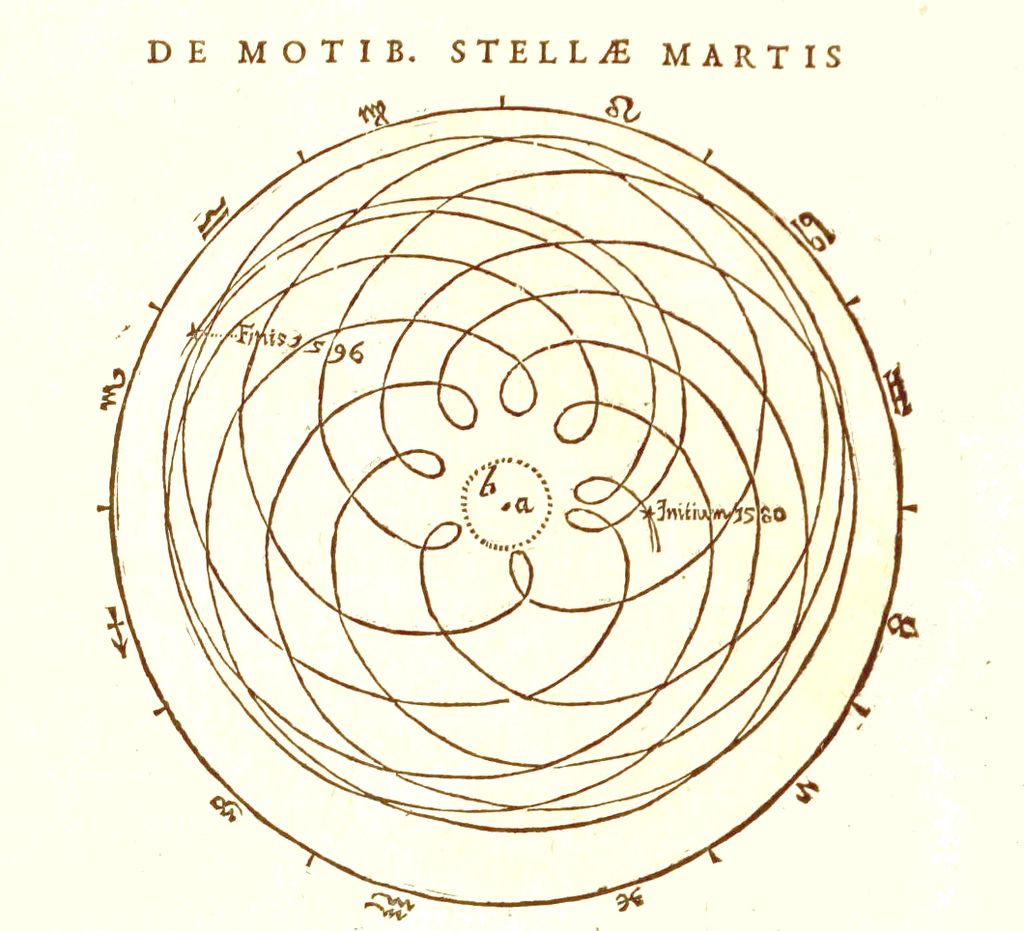

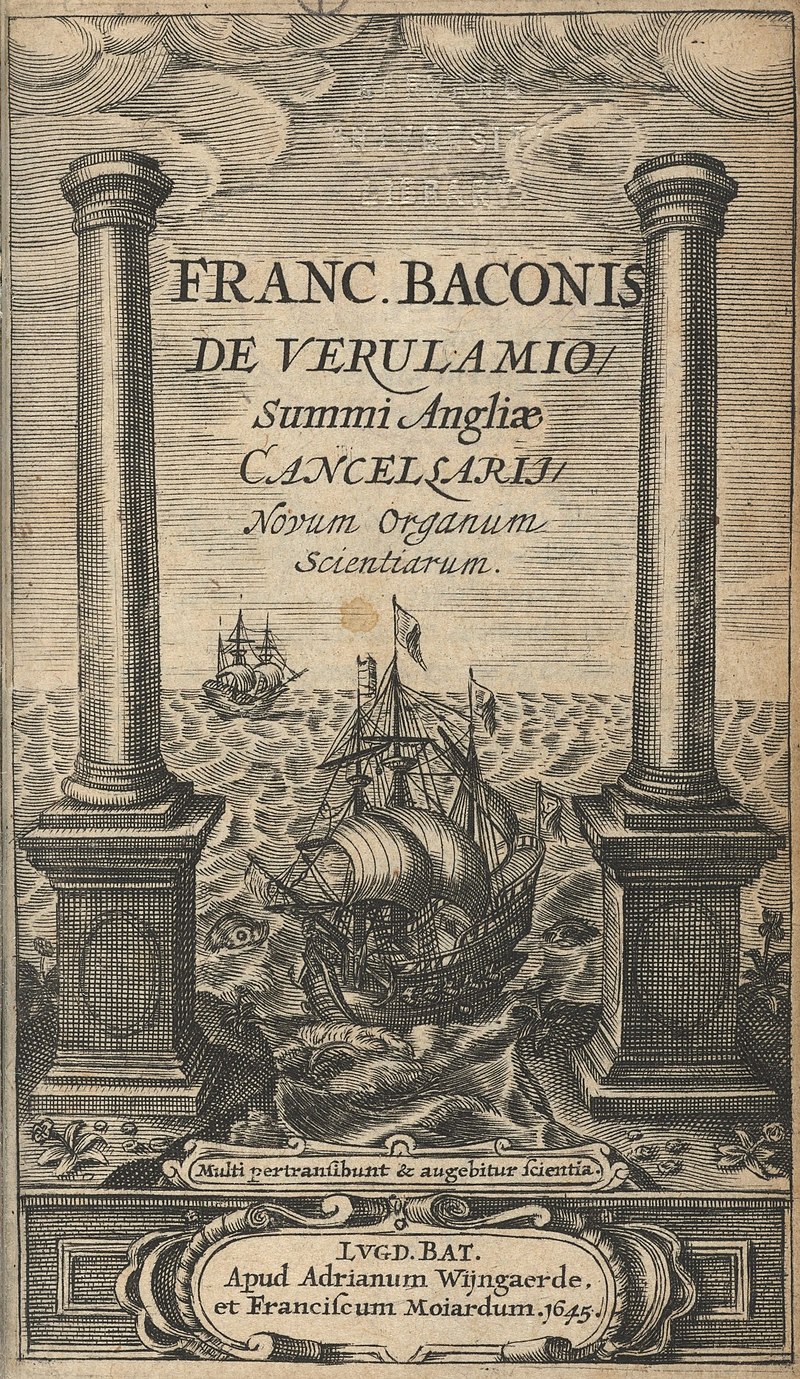

- 53 Early Science

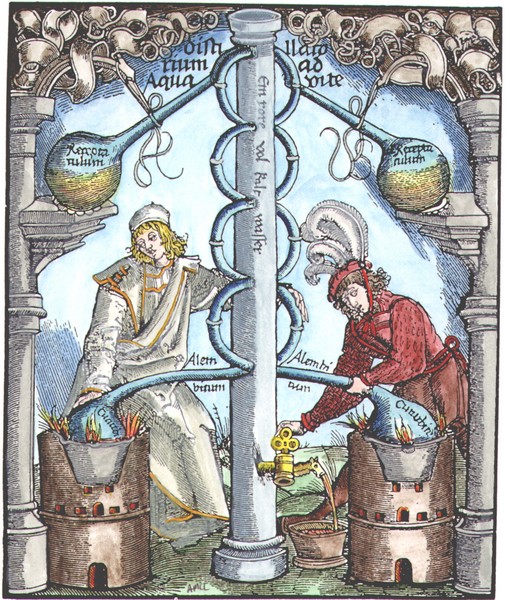

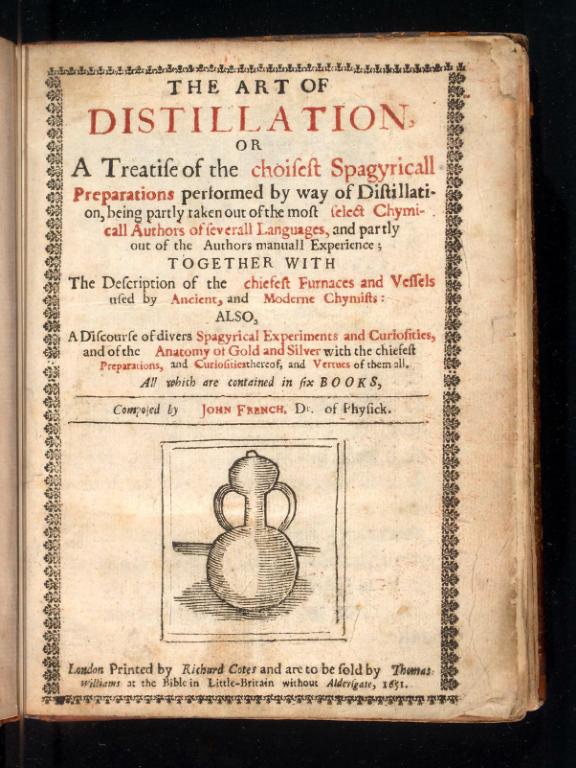

- 54 John French

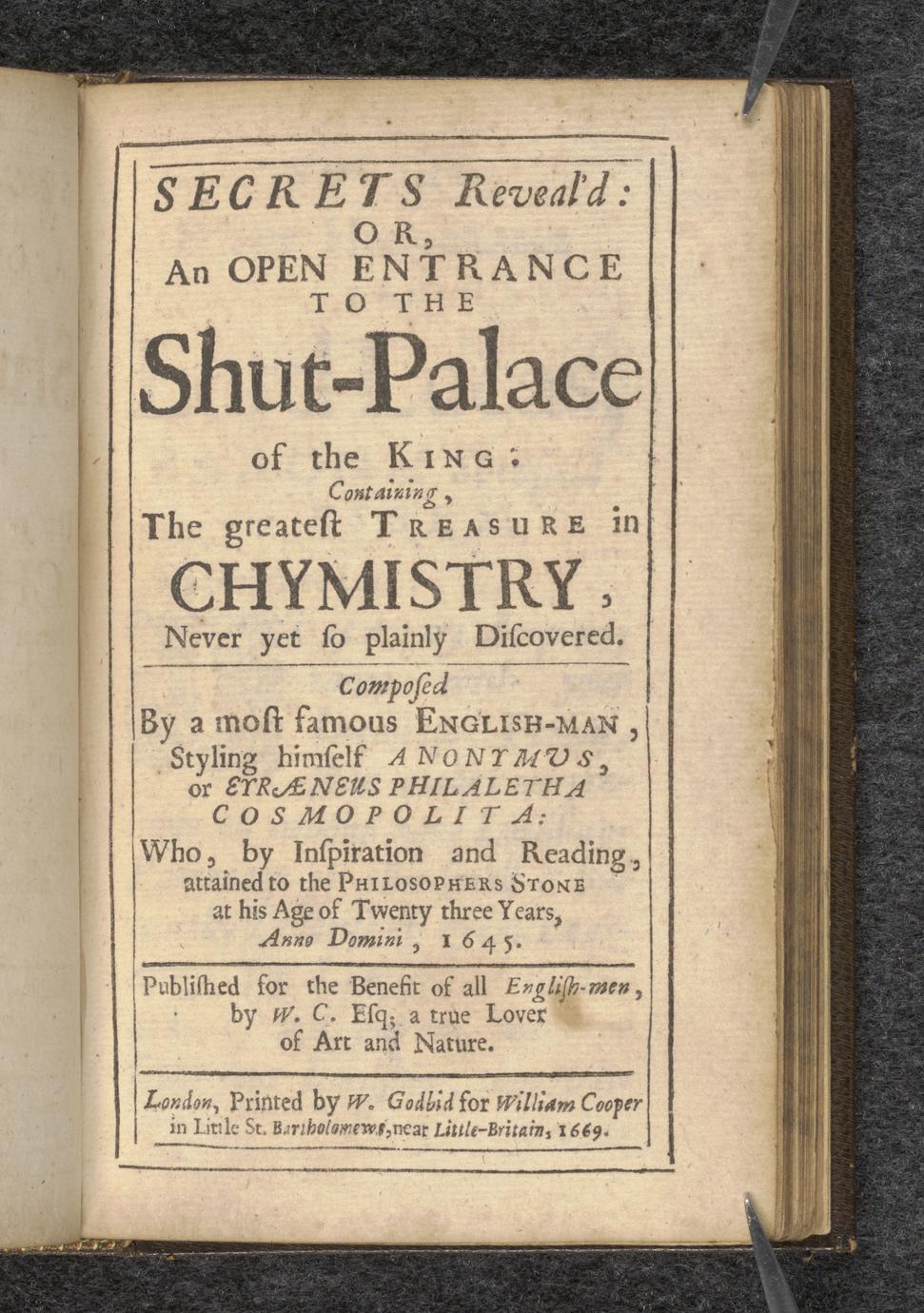

- 55 George Starkey

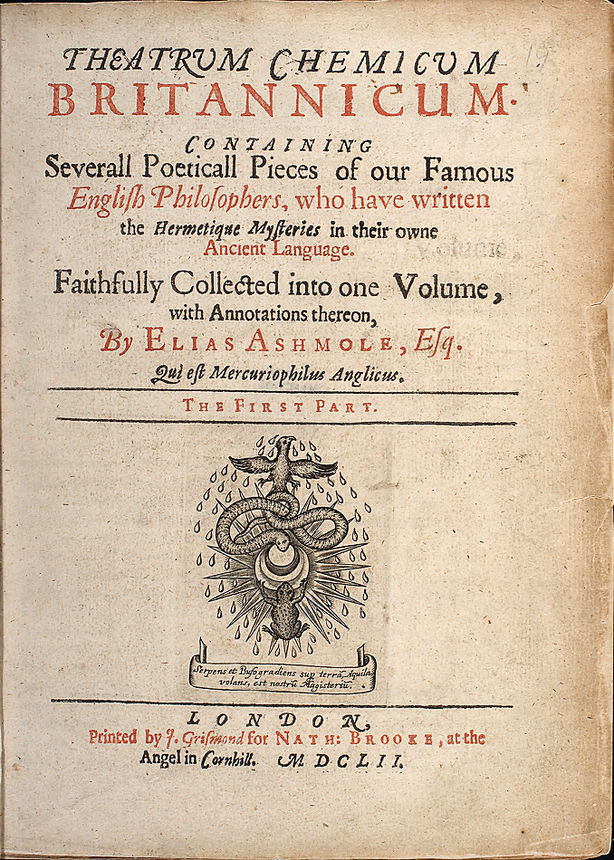

- 56 Elias Ashmole

- 57 Robert Boyle

- 58 Isaac Newton

- 59 The End of Alchemy

- 60 Why Did Alchemy Last?

- 61 What Did Alchemy Give Us?

- 62 Alchemy Today

Timeline of Alchemy

This is my timeline of Alchemy and all the influences it received and produced.

This is a work in progress. Links take you to my blog at https://blog.kf7k.com

Ancient dates are uncertain.

| 10000 BC | Invention of the plow and using domesticated draft animals to pull it allows villages to form, centering on crops and animal domestication. |

| 5000 BC | Towns form when food is abundant, supporting crafts like pottery and gold metallurgy, and early religious beliefs. Trade probably begins. Copper is smelted from ore. Dyeing with insect and vegetable dyes begins. pre-alchemy-alchemy-01 |

| 3500 BC | The wheel is invented, promoting trade and consequently local political power. By 3000 BC urbanized cities appear with cuneiform and Indus script to record transactions and stock. Crafts begin to diversify into artistic representational pottery, wall decoration with pigmented paints. pre-alchemy-alchemy-01 |

| 3000 BC | Tin is smelted from rare ores; when combined with 7 parts copper the resulting bronze is strong. The bronze trade expands across the Mediterranean by 2000 BC; the bronze age spans 1900 BC to 1100 BC. Trade booms: ivory and tin from Syria, copper from Sardinia and Cyprus, gold and alabaster from Egypt, pottery, cloth and olive oil from Greece and Crete. pre-alchemy-alchemy-01 |

| 2500 BC | Colored glass beads and glass mosaics are created in Lebanon, Mesopotamia, Egypt. Industrial-size trade by 1500 BC. |

| 2000 BC | Astrology is born from a combination of proto-astronomy and religion in the river valleys, where predicting floods from the sun's location in the heavens is key to planting at the right time. |

| 1500 BC | Writing had progressed from pictograms (Chinese scripts, Cuneiform scripts and hieroglyphs) to stylized cuneiform marks to the proto-Canaanite alphabet, probably in Egypt. Alphabets spread quickly, making writing and reading much easier, speeding the spread of ideas along bronze-age trade routes. |

| 1175 BC | Bronze age collapses when the Sea Peoples invade and destroy all urban centers in the Mediterranean. Egypt defends itself well. Climate change and earthquakes contribute. Trade ceases in the Mediterranean and the Levant. Civilizations begin to smelt iron because tin is no longer available. The biblical Philistines are one group of invaders who settle in the southern Levant (called Canaan in the Bible). |

| 800 BC | Iron-age wealth builds; trade restarts, driven primarily by the sea-faring Phoenicians, and cultural envy precipitates invasions. Assyria (in Anatolia, now Iraq and Turkey) dominates. |

| 650 BC | Zoroastrianism founded in Persia; embraces astrology and magic. astrology-and-magic-alchemy-07-interlude |

| 590 BC | Thales of Miletus (a Greek city in Turkey) postulates, from Egyptian creation myths, a theory that water is the primordial substance. Studies geometry, astronomy and philosophy, founds the Miletian school of philosophy. Miletian philosophers (Anaximines, Anaximander, etc) propose, in turn, earth, air, and fire as primordial elements. egyptian-creation-myths-as-interpreted-by-thales-of-miletus-alchemy-02 |

| 586 BC | Nebuchanezzar II leads Babylon and Persia against the Levant and Anatolia (Turkey) and into Greece. Hebrews exported as slaves to Mesopotamia (Iraq), to be released by Cyrus the Great in 539 BC but some stay as free men. |

| 540 BC | Pythagoras of Samos, near Miletus, excels in geometry, mathematics, numerology, and mysticism. |

| 490 BC | Darius I of Babylon, having taken all of Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Egypt, invades the Greek city-states; they defend themselves successfully. Xerxes, his son, tries to finish the invasion but withdraws in 480 BC. |

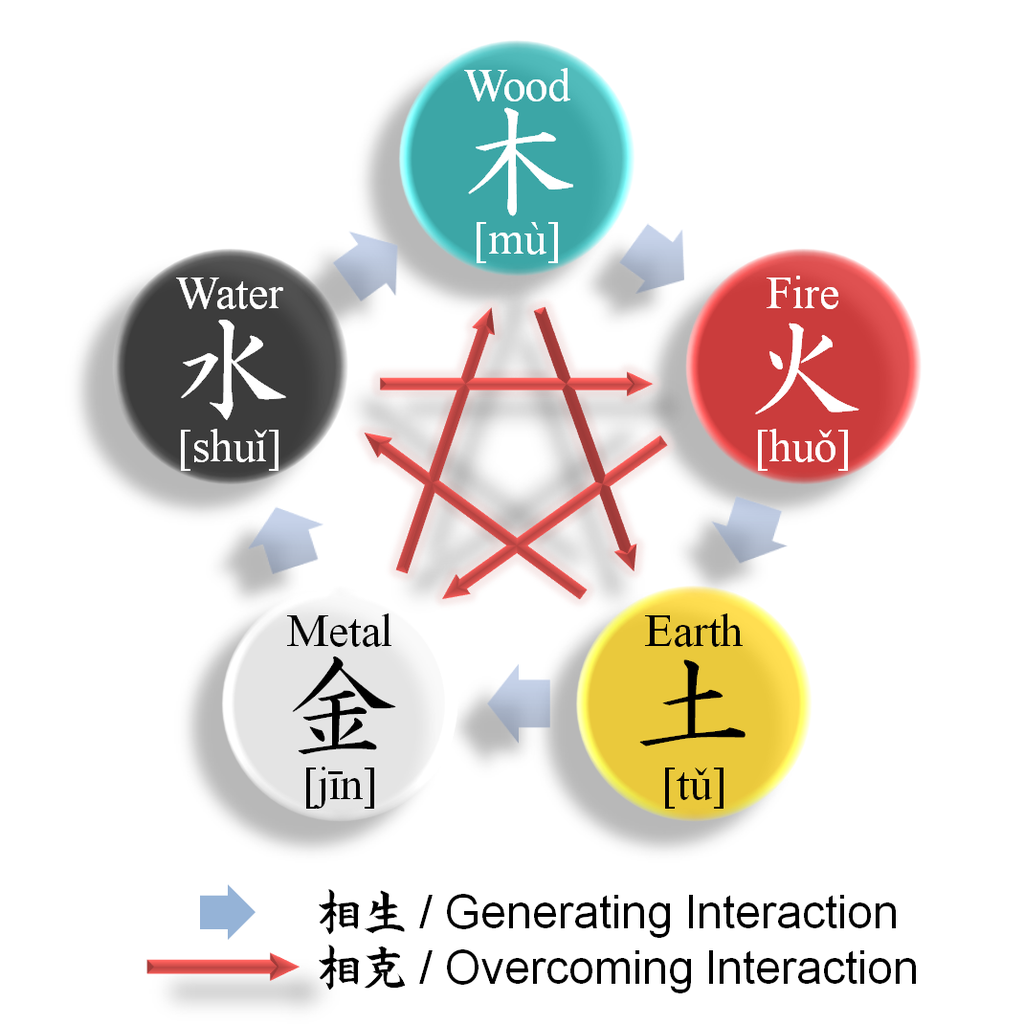

| 450 BC | Empedocles proposes there are four "elements" or primal forms of matter, Air, Water, Earth, Fire, as a capstone of the Miletian school. |

| 360 BC | Plato adopts the four-element theory with transmutations (using examples of phase changes), adding Prime Matter as matter which has no properties. He also introduces the idea of Being and Becoming: Being are things which are perfect, as God is perfect; Becoming are things endeavoring to be perfect, but which are still mortal. Into the Being category he places reason, into becoming he places observation. This puts reason as fundamental to interpreting the world, dismissing observation. plato-alchemy-03 |

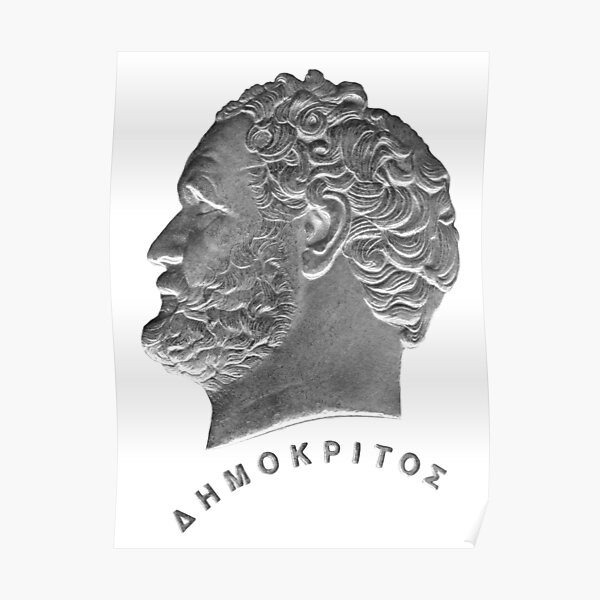

| 350 BC | Democritus proposes a theory of atoms, the indivisible smallest parts of matter, of unique shapes. Can't prove it. Plato and Aristotle ignore the idea. what-might-have-been-democritus-and-the-atomic-theory-alchemy-08-interlude |

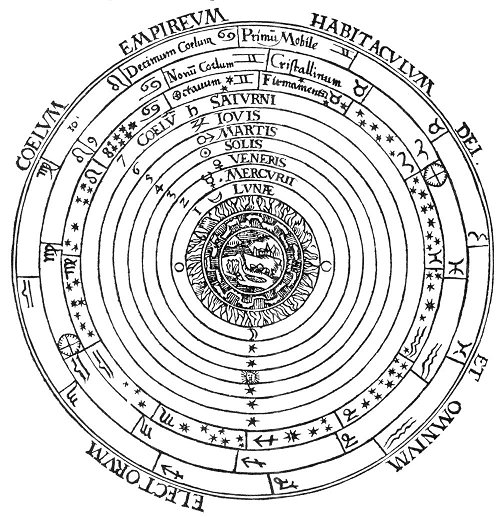

| 340 BC | Aristotle changes the four-elements theory to one related to properties (hot/cold, wet/dry) allowing the addition or subtraction of these properties to change the nature of the matter, or transmutation. He is very convincing and his ideas become the cornerstone of alchemy. Introduced æther as the fifth element, the element composing the heavens. Proposes a cosmology later influencing the Gnostics strongly. aristotle-alchemy-04 |

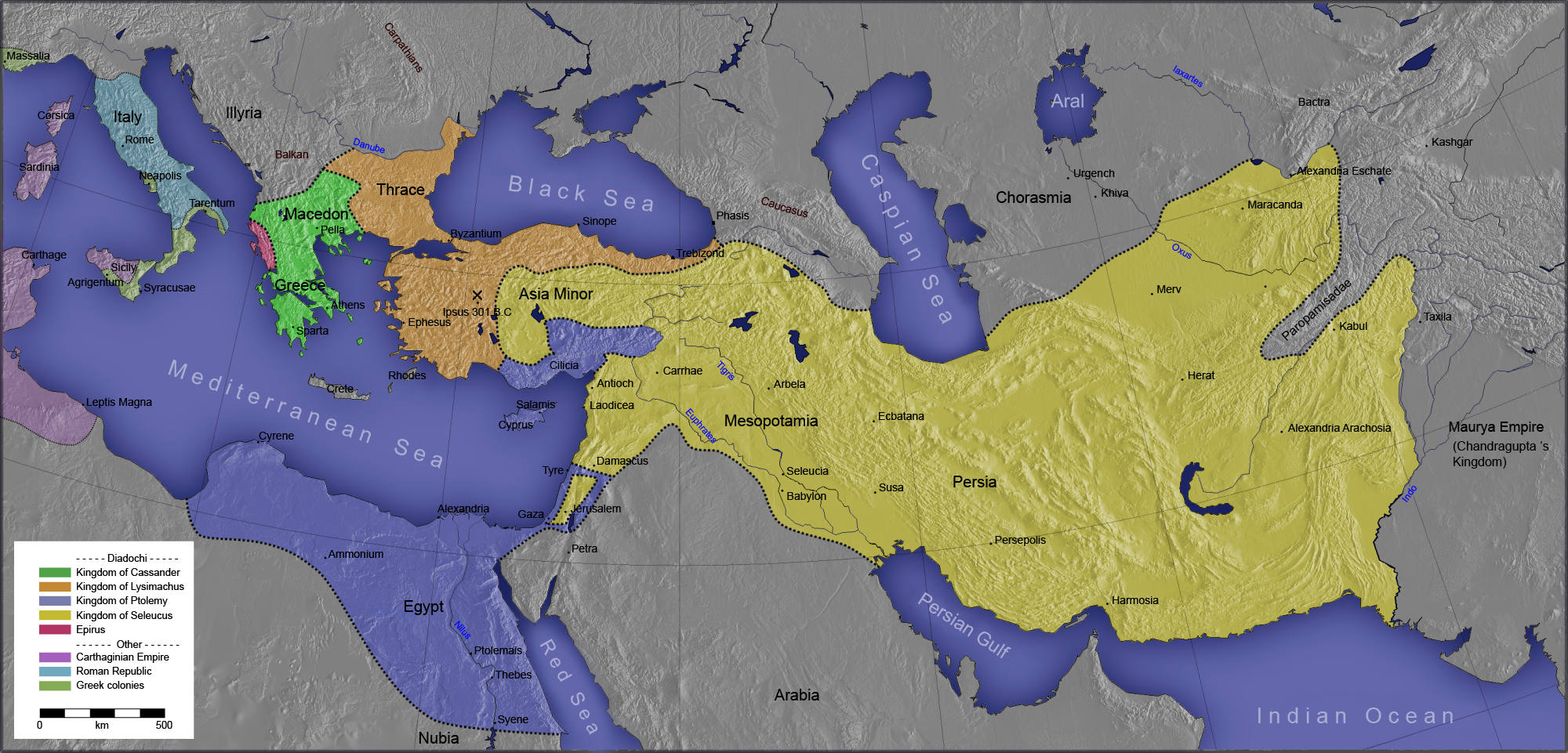

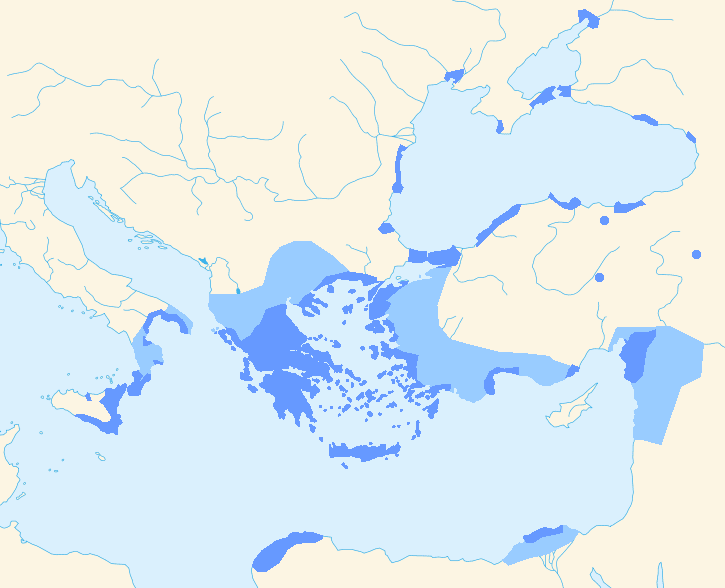

| 334 BC | Alexander the Great, pupil of Aristotle, conquers all the lands the Persians held and more, from Rome to Tibet. Established trade on an immense scale using Koine (common) Greek. Aristotle's ideas were carried from Italy to China. Founds Alexandria, a trade port in the Nile Delta. alexander-the-great-spreading-ideas-alchemy-06 a-note-on-translations-from-the-greek-alchemy-10-interlude |

| 300 BC | Theophrastus, a follower of Aristotle, studies botany and the uses of plants in medicine. |

| 221 BC | Shih Huang Ti, first emperor of China, legendary founder of alchemy in China, believed wuxing, the five-element theory. |

| 100 BC | Ssu-ma Ch’ien, historian, first mention of alchemy in Chinese literature |

| 32 AD | Jesus founds Christianity |

| 100 AD | Gnostic ideas begin in Israel and Egypt as a blend of Aristotelean cosmology, Christianity, Jewish mysticism, Copic religion, and Zoroastiran astrology. gnosticism-alchemy-14-interlude |

| 100 AD | Pseudo-Democritus the alchemist: Recipes for coloring or alloying base metals. Contains the first hints at two important concepts: the process is more important than the materials used, and alchemists are doing what nature does, only faster. the-beginning-of-alchemy-psuedo-democritus-alchemy-09 |

| 100 AD | Mary the Jewess: experimental alchemist, invented early alchemical equipment |

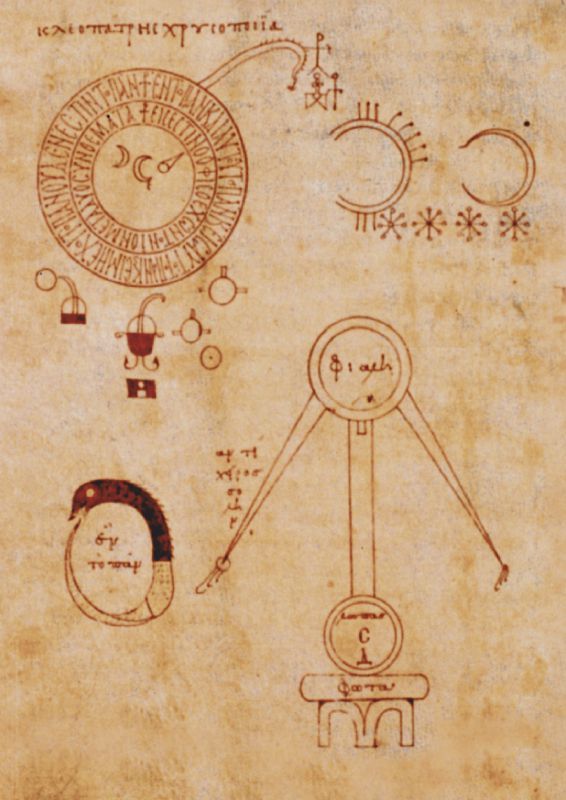

| 150 AD | Cleopatra the Alchemist, experimental alchemist the-dialog-of-cleopatra-and-the-philosophers-alchemy-11 |

| 200 AD | Composition of the Corpus Hermeticum, a collection of several Greek texts from the second and third centuries, survivors from a more extensive literature, known as the Hermetica. hermes-trismegistus-alchemy-15 |

| 296 AD | Diocletian, Roman emperor, bans alchemy perhaps to control the economy, but alchemy continues in the Roman-controlled Alexandria, Egypt |

| 300 AD | Earliest chemical recipes with alchemical outcomes written the-earliest-chemistry-alchemy-12 |

| 300 AD | Zosimos of Panopolis (Hellenistic alchemist) writer of one of the oldest surviving alchemical tractates, introduces pure allegorical descriptions of alchemical processes the-visions-of-alchemy-alchemy-13 |

| 600 AD | Stephanos of Alexandria, a public speaker, speaks rhapsodically about alchemy stephanos-of-alexandria-alchemy-16 |

| 642 AD | The Muslims invade Egypt, pass through Oxyrhynchus and dump all the library records. They appear to keep Plato and Aristotle and any alchemical writings they find. oxyrynchus-and-the-rise-of-islam-alchemy-24-interlude |

| 650 AD | Khalid Ibn Yazeed, Arabic Alchemist, summarized Greek alchemy khalid-ibn-yazid-alchemy-25 |

| 700 AD | 8th century. Copy of an Alexandrian manuscript (which?) gives first recorded mention of the word Vitriol. The same document gives first mention of cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) |

| 776 AD | Jabir, the Arabian alchemist whose real name has been variously stated as Abu Musu Jabir ibn Haiyan or Abou Moussah Djafar al Sofi, is active. According to the tenth-century Kitab-al-Fihrist, Jabir was born at Tarsus and lived at Damascus and Kufa. jabir-ibn-hayyan-alchemy-26 what-jabir-said-alchemy-27-interlude |

| 800 AD | Alchemy, combined with medicine and yoga, printed in India. The practice may have predated the earliest texts we have. indian-alchemy-alchemy-21 |

| 900 AD | Al-Tamimi Muhammad Ibn Umayl, Arabic Alchemist ibn-umayl-alchemy-28 |

| 940 AD | Ibn Wahshiyh, Abu Baker, "Rhazes" Arabic Alchemist and botanist al-razi-alchemy-29 |

| 950 CE | Al Majrett’ti Abu-al Qasim, Arabic alchemist and astrologer |

| 954 CE | Alfarabi, an Arab Alchemist |

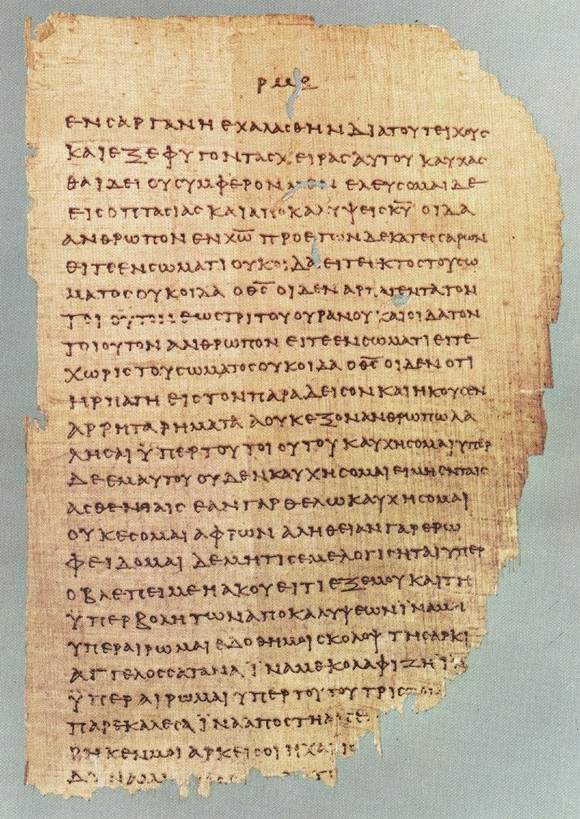

| 1000 CE | Codex Marcianus 299: Earliest surviving Greek alchemical manuscript |

| 1010 CE | Abu Ali Sina, "Avicenna", an Arab physician avicenna-alchemy-30 |

| 1054 CE | Rome splits from orthodox church, forms Catholic church |

| 1099 CE | Godfri de Bouillion takes Jerusalem as part of the crusades. |

| 1100 CE | Al-Tuhra-ee, Al-Husain Ibn Ali, Arabic Alchemist |

| 1144 CE | Earliest dated Western alchemical treatise - Robert of Chester De compositione alchemiae |

| 1150 CE | Turba philosophorum translated from Arabic in the Toledo School of the Translators |

| 1160 CE | Artephius (alchemist) asserts in his ‘Secret Book’ that he has lived for 1000 years before this date due to his use of the Elixir of Life. |

| 1199 CE | Approximate date Grail romances appeared in Western Europe |

| 1231 CE | First mention of alchemy in French literature - Roman de la Rose. William de Loris writes Le Roman de Rose, assisted by Jean de Meung, who also wrote The Remonstrance of Nature to the Wandering Alchemist and The Reply of the Alchemist to Nature |

| 1235 CE | Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, discusses transmutation of metals in De artibus liberalibus and De generatione stellarum. |

| 1248 CE | Albertus Magnus, alchemist, Dominican Monk, well-respected philosopher, publishes his version of Arabic alchemy, and his study of minerals and ores. albertus-magnus-alchemy-32 |

| 1256 CE | King Alfonso the Wise of Castile orders translation of alchemical texts from Arabic. He is supposed to have written Tesoro a treatise on the Philosophers’ stone |

| 1267 CE | Roger Bacon, alchemist, occultist and Franciscan friar, is born. Bacon, also known as Doctor Mirabilis (Latin: ‘wonderful teacher’), eventually places considerable emphasis on empiricism and becomes one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method. roger-bacon-alchemy-33 |

| 1270 CE | Thomas Aquinas, pupil of Albertus, is sympathetic to the idea of alchemical transmutation in his Summa theologia. In his Thesaurus Alchimae, Aquinus speaks openly of the successes of Albertus and himself in the art of transmutation. |

| 1272 CE | Provincal Chapter at Narbonne forbids the Franciscans to practice alchemy. |

| 1275 Ce | Raymond Lull, actually not an alchemist, believed to possess titanic physical and mental energy, who threw himself heart and soul into everything he did, is born. Writings attributed to Lull include a number of works on alchemy, most notably Alchimia Magic Naturalis, De Aquis Super Accurtationes, De Secretis Medicina Magna and De Conservatione Vitoe, Ars Magna. raymond-lull-alchemy-35 |

| 1280 CE | Sefer Ha-Zohar, an essential Qabalistic text, makes its first written appearance, written by Moses de León but attributed to Simon ben Yohai. |

| 1285 CE | Arnold of Villanova, physician and alchemist. His lengthy book The Treasure of Treasures, Rosary of the Philosophers, and Greatest Secret of all Secrets highly influential and popular. arnold-of-villanova-alchemy-34 |

| 1298 CE | Alain de Lisle. There are also earlier accounts of Alanus de Insulis, born in Rijssel in 1114 CE in the Netherlands, later abbot of Clairvaux and bishop of Auxerne |

| 1310 CE | Al-Jildaki, Muhammad Ibn Aidamer, Arabic Alchemist which shared knowledge with certain Templars |

| 1312 CE | The Knights Templar become extinct, except for a few, when the order is dissolved by the Council of Vienne. All the property owned by the Templars is transferred to the Knights of St. John (The Hospitallers) |

| 1314 CE | Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Knights Templar, is burned at the stake |

| 1317 CE | The first Rosicrucian order is formed: the French Ordre Souverain des. Frères Aînés de la Rose Croix |

| 1317 CE | Pope John XXII’s Papal Bull, Spondet quas non exhibent, is issued against those who practice alchemy. The Cistercians ban alchemy. John Dunstin defends. john-dastin-and-the-pope-alchemy-38 |

| 1323 CE | Dominicans in France prohibit the teaching of alchemy at the University of Paris, and demand the burning of alchemical writings |

| 1329 CE | King Edward III requests Thomas Cary to find two alchemists who have escaped, and to find the secret of their art |

| 1330 CE | Nicolas Flamel is born. Flamel becomes a successful writer, manuscript-seller, and alchemist. Flamel is attributed as the author of the Livre des Figures Hiéroglypiques, an alchemical book published in Paris in 1612 then in London in 1624 as ‘Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures.’ Flamel is reputed to have succeeded in the two goals of Hermetic alchemy - to have made the Philosopher’s Stone which turns lead into gold, and to have achieved immortality in a single incarnation, together his wife Perenelle. Pope John XXII gives funds to his physician to set up a laboratory for a ‘certain secret work.’ |

| 1338 CE | Hospitallers acquire Templar Holdings in Scotland |

| 1340 CE | Jean de Meung, author of the Romance of the Rose |

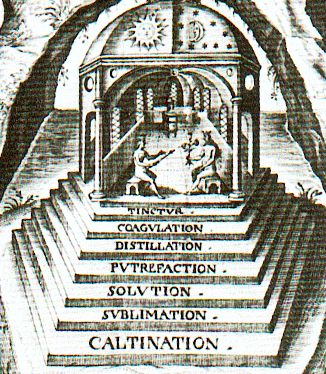

| 1356 CE | Pope Innocent VI imprisons the Catalan alchemist John of Rupescissa, who insists that the only real purpose of alchemy is to benefit mankind. Rupescissa’s works abound with medicinal preparations derived from metals and minerals and he emphasizes distillation processes which seemingly separate pure quintessences from the gross matter of natural substances. |

| 1357 CE | Hortulanus’ commentary on the Emerald Tablet of Hermes |

| 1376 CE | The Dominican Directorium inquisitorum, the textbook for inquisitors, places alchemists among magicians and wizards. |

| 1380 CE | King Charles V the Wise issues a decree forbidding alchemical experiments |

| 1380 CE | Bernard of Trevisa |

| 1388 CE | Geoffrey Chaucer Canterbury Tales discussed alchemy in the Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale alchemical-cons-the-canons-yeomans-tale-alchemy-40 |

| 1398 CE | Supposed date that Christian Rosencruez founds Rosicrucian Order |

| 1403 CE | King Henry IV of England issues a prohibition of alchemy and to stop counterfeit money |

| 1450 CE | Basil Valentine, prior of a Benedictine monastry |

| 1453 CE | Joost Balbian, Dutch alchemist born in Aalst, died in 1616 in Gouda |

| 1456 CE | 12 men petition Henry VI of England for a license to practise alchemy |

| 1470 CE | Der Antichrist und die funfzehn Zeichnen (the book of the antichrist) associates alchemists with demons and Satan |

| 1471 CE | George Ripley Compound of alchemy. Ficino’s translation of the Corpus Hermeticum |

| 1476 CE | George Ripley writes Medulla alchemiae. |

| 1485 CE | Summa perfectionis, attributed to Geber, is published. In this important alchemical text, the sulphur-mercury theory forms the theoretical basis for an understanding of the metals, and the alchemist is informed that he must arrange these substances in perfect proportions for the consummation of the Great Work. Geber describes in considerable detail the laboratory processes and equipment of the alchemist |

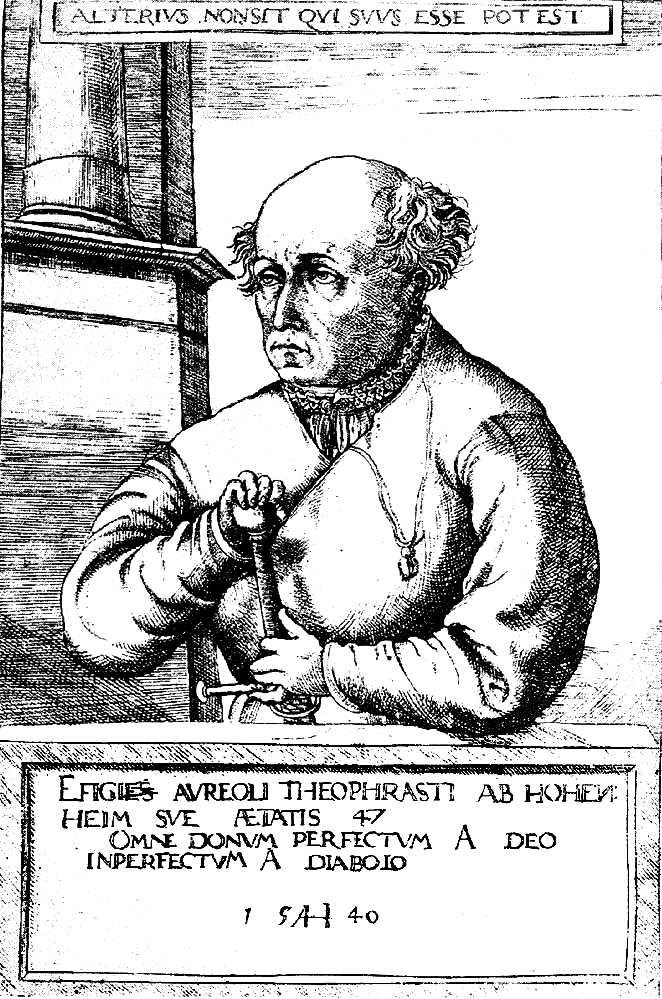

| 1493 CE | Paracelsus, alchemist, physician, astrologer, and general occultist, is born. Born Phillip von Hohenheim, he later takes up the name Philippus Theophrastus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim, and still later takes the title, Paracelsus, meaning ‘equal to or greater than Celsus.’ Celsus was a Roman encyclopedist from the first century known for his tract on medicine. |

| 1530 CE | Georgius Agricola Bermannus, book on mining and extraction of ores |

| 1532 CE | The earliest version of the Splendor Solis, one of the most beautiful of illuminated alchemical manuscripts, part of an illustrated book trend called Emblem Books. The work consists of a sequence of 22 elaborate images, set in ornamental borders and niches. The symbolic process shows the classical alchemical death and rebirth of the king, and incorporates a series of seven flasks, each associated with one of the planets. Within the flasks a process is shown involving the transformation of bird and animal symbols into the Queen and King, the white and the red tincture. |

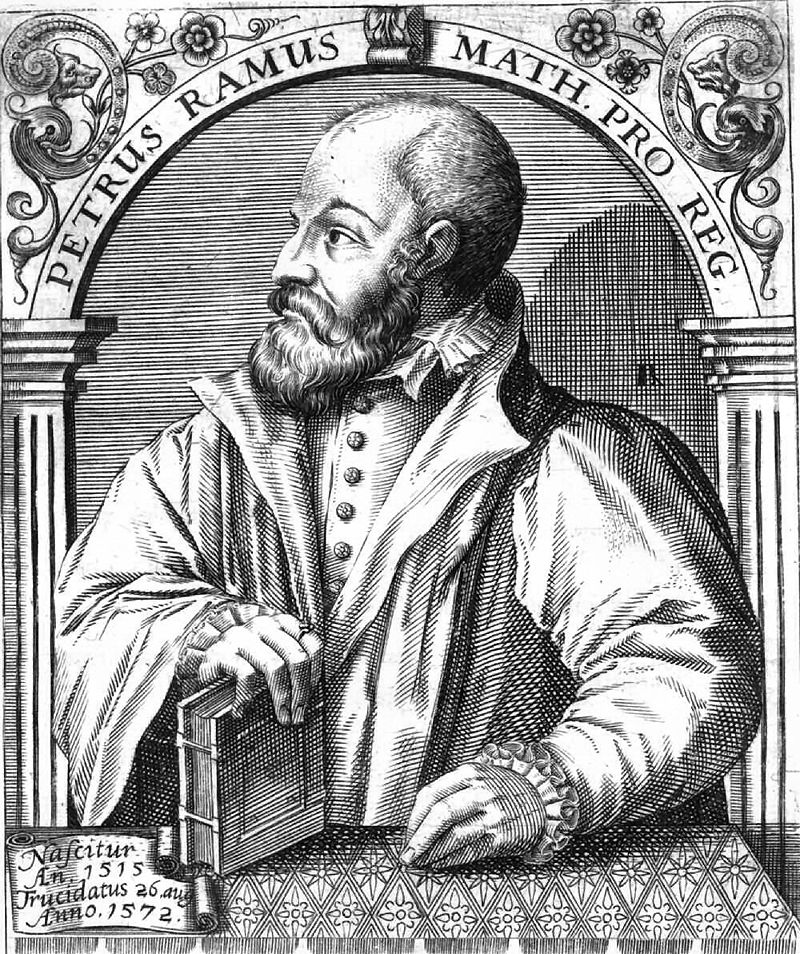

| 1536 CE | Petrus Ramus (Peter rami) publishes his thesis, translated as "Everything Aristotle Said Was Wrong." First break with the tradition of Aristotle as the smartest man who ever lived. |

| 1540 CE | Paracelsus, physician and alchemist |

| 1541 CE | In hoc volumine alchemia first alchemical compendium |

| 1550 CE | The Rosarium philosophorum, attributed to Attributed to Arnoldo di Villanova (1235-1315), is first published, although it had circulated in manuscript form for centuries. |

| 1552 CE | Emperor Rudolph II is born. Astronomy and alchemy become mainstream science in Renaissance Prague and Rudolf was a firm devotee of both. His lifelong quest is to find the Philosophers Stone and Rudolf spares no expense in bringing Europe’s best alchemists to court, such as Edward Kelley and John Dee. Rudolf even performs his own experiments in a private alchemical laboratory. |

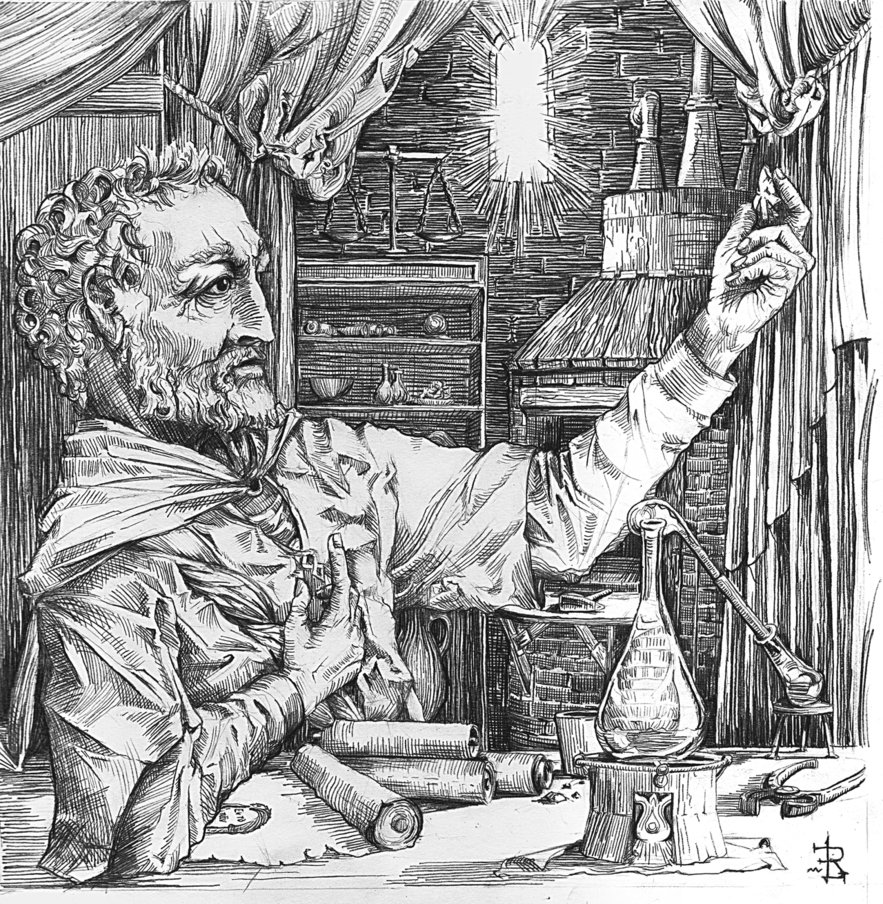

| 1560 CE | Heinrich Khunrath is born in Leipzig. It is evident that the first Rosicrucian manifesto, the Fama Fraternitatis, is influenced by the work of this respected Hermetic philosopher and author of "Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae" (1609), a work on the mystical aspects of alchemy, which contains the oft-seen engraving entitled ‘The First Stage of the Great Work’, better-known as the ‘Alchemist’s Laboratory.’ |

| 1566 CE | Michael Maier, Rosicrucian alchemist, and philosopher, physician to Emperor Rudolph II, is born. Meier becomes one of the most prominent defenders of the Rosicrucians, clearly transmitting details about the "Brothers of the Rose Cross" in his writings. |

| 1571 CE | Johannes Pontanus, born in Hardewijk, the Netherlands, studied the path of Arthepius together with Tycho Brahe. Died in 1640 |

| 1589 CE | Edward Kelley embarkes on his public alchemical transmutations in Prague |

| 1599 CE | First appearance of a work of Basil Valentine, the German adept and Benedictine monk, in alchemical philosophy is commonly supposed to have been born at Mayence toward the close of the fourteenth century. His works will eventually include the Triumphant Chariot of Antimony, Apocalypsis Chymica, De Microcosmo degue Magno Mundi Mysterio et Medecina Hominis and Practica un cum duodecim Clavibus et Appendice. |

| 1608 CE | Seton the cosmopolite |

| 1608 CE | John Dee, an English clergyman |

| 1612 CE | Flamel figures hierogliphiques first published. Ruland’s Lexicon alchemiae. |

| 1614 CE | The Fama Fraternitas, the first Rosicrucian manifesto is published. The Rosicrucian manifestos, Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis (1614), Confessio Fraternitatis (1615), and Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz (1616) cause immense excitement throughout Europe. |

| 1620 CE | Jean d’Espagnet, author of the Hermetic Arcanum |

| 1626 CE | Goosen van Vreeswyk, the Dutch mountain master. Died in 1690 |

| 1636 CE | Michael Sendivogius |

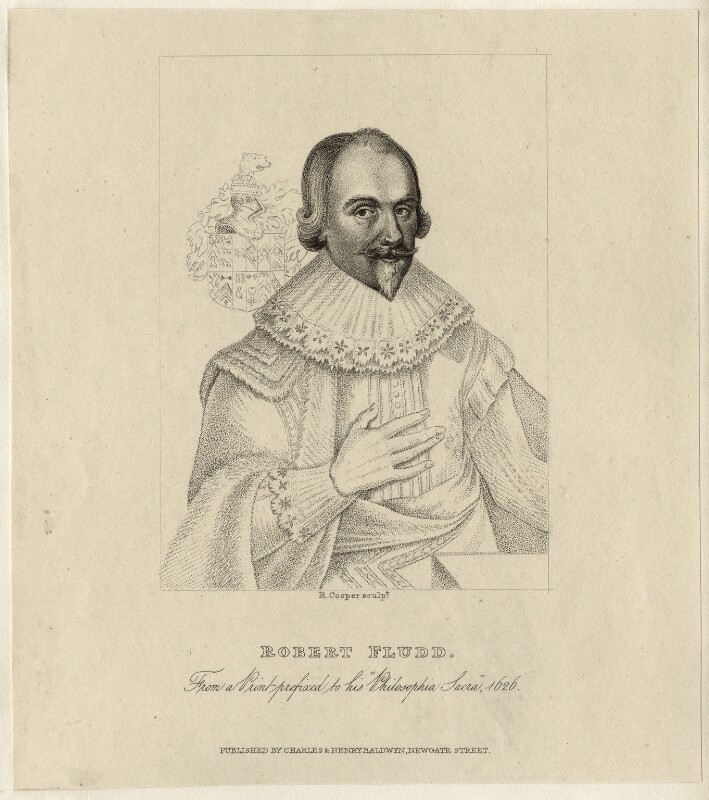

| 1638 CE | Robert Fludd, theologican and mystic |

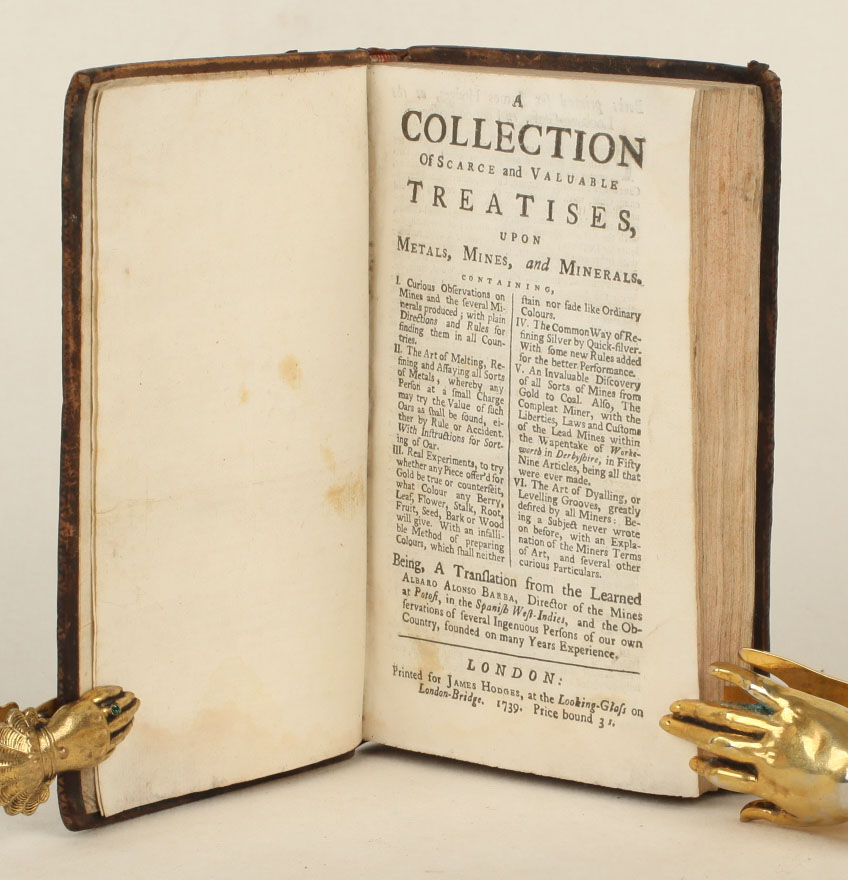

| 1640 CE | Albaro Alonso Barba Art of metals |

| 1643 CE | Johannes van Helmont |

| 1646 CE | George Starkey |

| 1648 CE | Elias Ashmole, the antiquarian |

| 1650 CE | Rudolf Glauber, physician |

| 1652 CE | Georg von Welling, a Bavarian alchemical and theosophical writer, is born. Von Welling is known for his 1719 work Opus Mago-Cabalisticum et Theosophicum. |

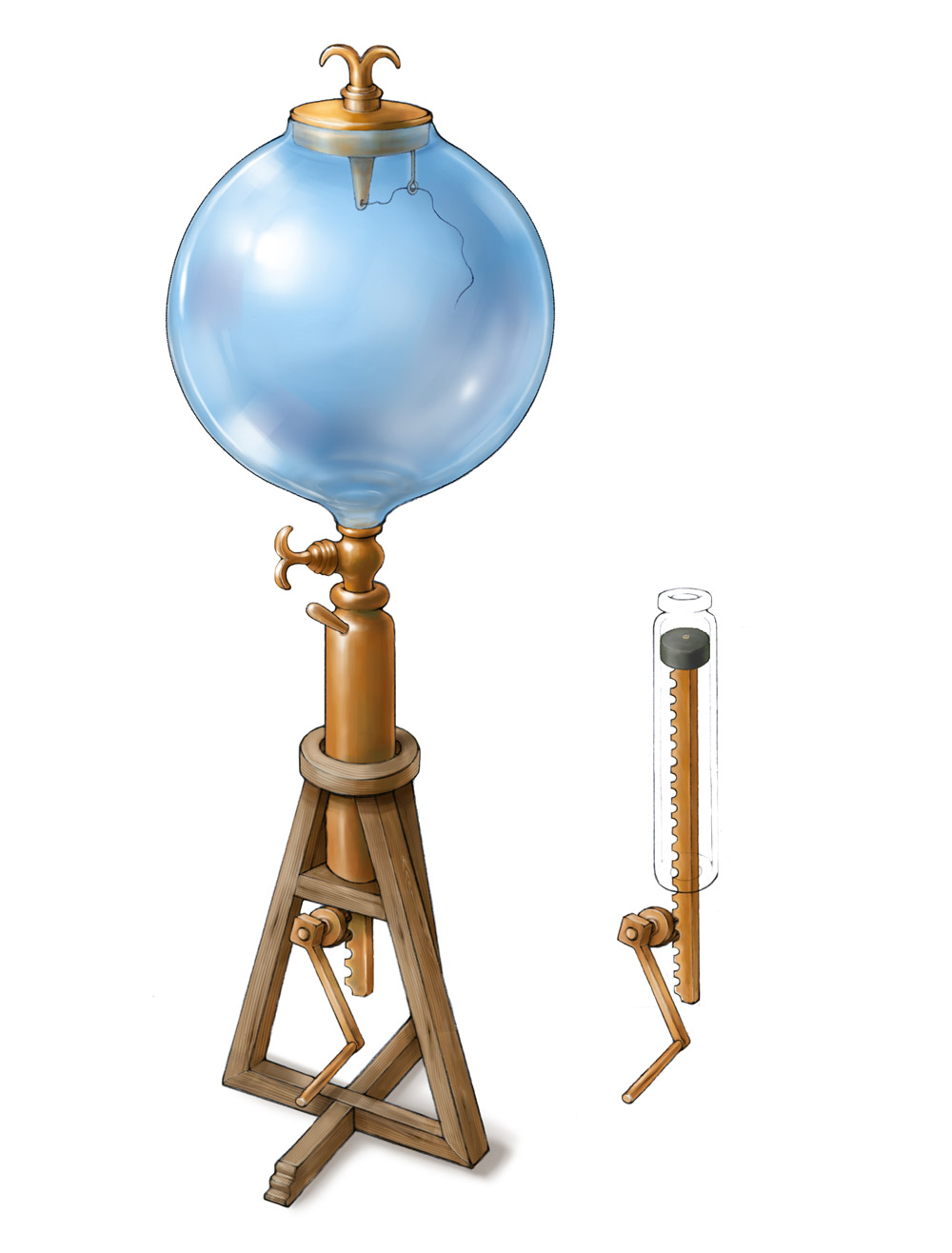

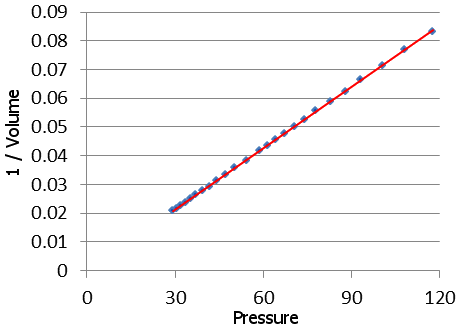

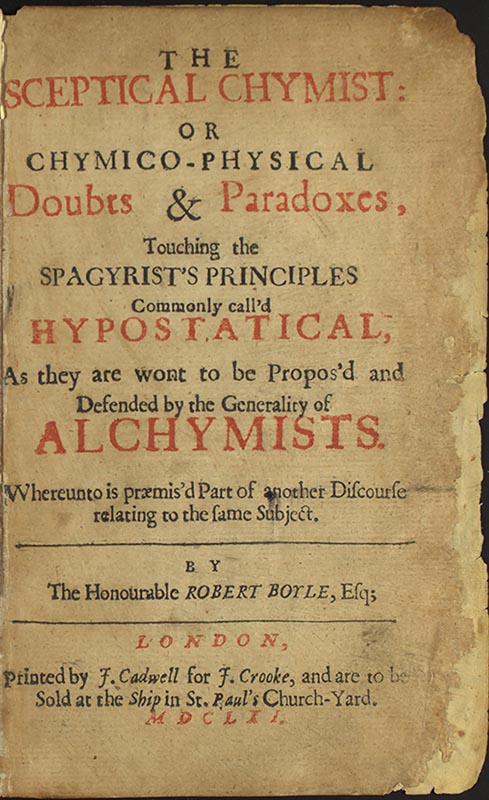

| 1661 CE | Robert Boyle publishes Skeptycal Chymist, a dialog against Paracelsian alchemy. Boyle continues as an alchemist another 5 years at least. |

| 1662 CE | Robert Boyle conducts first scientific experiment, finds Law of Gasses. |

| 1666 CE | Helvetius’ account of the transmutation in the Hague. Crassellame Lux obnubilata |

| 1667 CE | Johan de Monte Snijder performed a transmuation in 1667 for Guillaume in Aken, the Netherlands |

| 1667 CE | Eirenaeus Philalethes An open entrance to the closed palace of the King |

| 1675 CE | Olaus Borrichius |

| 1677 CE | Mutus Liber |

| 1680 CE | Isaac Newton begins his study of alchemy, continues until he dies. |

| 1690 CE | Publication of the English translation of the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz |

| 1691 CE | Birth of Saint Germain |

| 1710 CE | Samuel Richter begins to form the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross |

| Lascaris, A greek Adept / monk that live in the Netherlands for a while, and thereafter went to Berlin, where he gave J.F. Böttger the stone | |

| 1717 CE | Grand Lodge of English Freemasonry founded |

| 1719 CE | Georg von Welling’s "Opus Mago-Cabalisticum et Theosophicum" is published. This is an important and influential esoteric work, which influences numerous subsequent authors, including Goethe, who perused it during his alchemical studies. |

| 1723 CE | The Golden Chain of Homer, written or edited by Anton Josef Kirchweger, is first issued at Frankfurt and Leipzig in four German editions in 1723, 1728, 1738 and 1757. A Latin version is issued at Frankfurt in 1762, and further German editions follow. This work has an enormous influence on Rosicrucan alchemy and on the Golden and Rosy Cross order. In the late eighteenth century |

| 1735 CE | Abraham Eleazar Uraltes chymisches Werck |

| 1739 CE | Matthieu Dammy, one of the last famous Parisian Alchymists, published his works in Amsterdam |

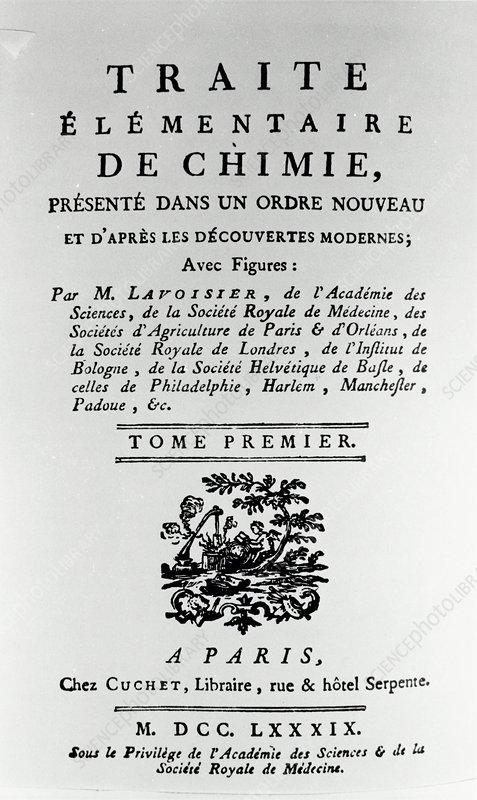

| 1779 CE | Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier assembles the coffin for alchemy by making exact measurements of chemical reactions. He is fundamental in establishing the nomenclature of chemistry. |

| 1805 CE | John Dalton nails the lid on alchemy's coffin when he publishes his atomic theory. |

I am assisted for the dates by History of the World Map by Map, 2018, DK/Penguin Random House.

Basic format and many entries from https://innergarden.org/en/time.html

01 Pre-alchemy

What is known of how much chemistry was done before 600 BC?

Lots, and none. We have artifacts. Lots of them. Glass from Egypt.

Clays and potteries from everywhere.

Metals from India, Persia, and all around the Old World. Even some early samples of steel. Gold and silver working. Lots of copper, some zinc, thus some bronze.

We have paints, glazes, dyes. There is soap.

And we don't have a single word on how any of it was made. The manufacture of all these things seemed to be ensconced firmly in the crafts. No one was asking "Why?" or "How?" They just made it, probably passed from master to apprentice. No instructions exist. Nothing but what they made.

Pottery required multi-stage firings, taking advantage of oxidizing and reducing furnaces to get the blacks and the lighter shades to both give purer colors.

Dying and metallurgy were probably the most difficult, with glassmaking and paint close behind.

Dying requires a good permanent dye, and a mordant to make it stick to the leather or cloth fibers. Once you have them by experimentation, you have a good method. Then you simply need a good source of supplies. The dyes came from plants or insects. The mordant was typically something like alum, KAl(SO4)2 . 12H2O. Use the trade routes to get it in from the distant lands where it was mined. Some of the dyes needed to be shipped in also, when the plant or insect was found only far away.

Metallurgy is straightforward when you have the ore close by. Most was done using charcoal (wood heated in the absence of air) and bellows to blow it hot. Iron was possible bit needed a very hot fire. Steel was made probably by accident in a few locations. Most of the metallurgy was copper and tin, which combined to make bronze. Bronze was hard and workable, and the bronze age sword was state of the art for a very long time. But tin is hard to find because it is rather more soluble in water than most metal ores. Gold and silver smithing was more common because, well, looks and longevity.

Glass making requires sand, borax, and trace metal ores for color. And a very hot flame. And a pot to melt it in. Early Egyptian glass was mostly flat-poured glass. No vessels or shaped items, just flat cracked colored glass.

All this we know because we have it in museums and have studied it.

Paint was known, but required brilliant minerals you grind and combine with egg whites to make them stick to surfaces. It doesn't work perfectly, and most painted items don't look painted anymore, so it has a darkened past.

Alchemy probably had something of a start in these crafts, but alchemy went an entirely different direction than making pretty things.

It first needed philosophy.

02 Thales of Miletus: Egyptian Creation Myths?

There are four Egyptian creation myths, all similar.

The different creation myths have some elements in common. They all held that the world had arisen out of the lifeless waters of chaos, called Nu. They also included a pyramid-shaped mound, called the benben, which was the first thing to emerge from the waters. These elements were likely inspired by the flooding of the Nile River each year; the receding floodwaters left fertile soil in their wake, and the Egyptians may have equated this with the emergence of life from the primeval chaos. The imagery of the pyramidal mound derived from the highest mounds of earth emerging as the river receded.

Wikipedia

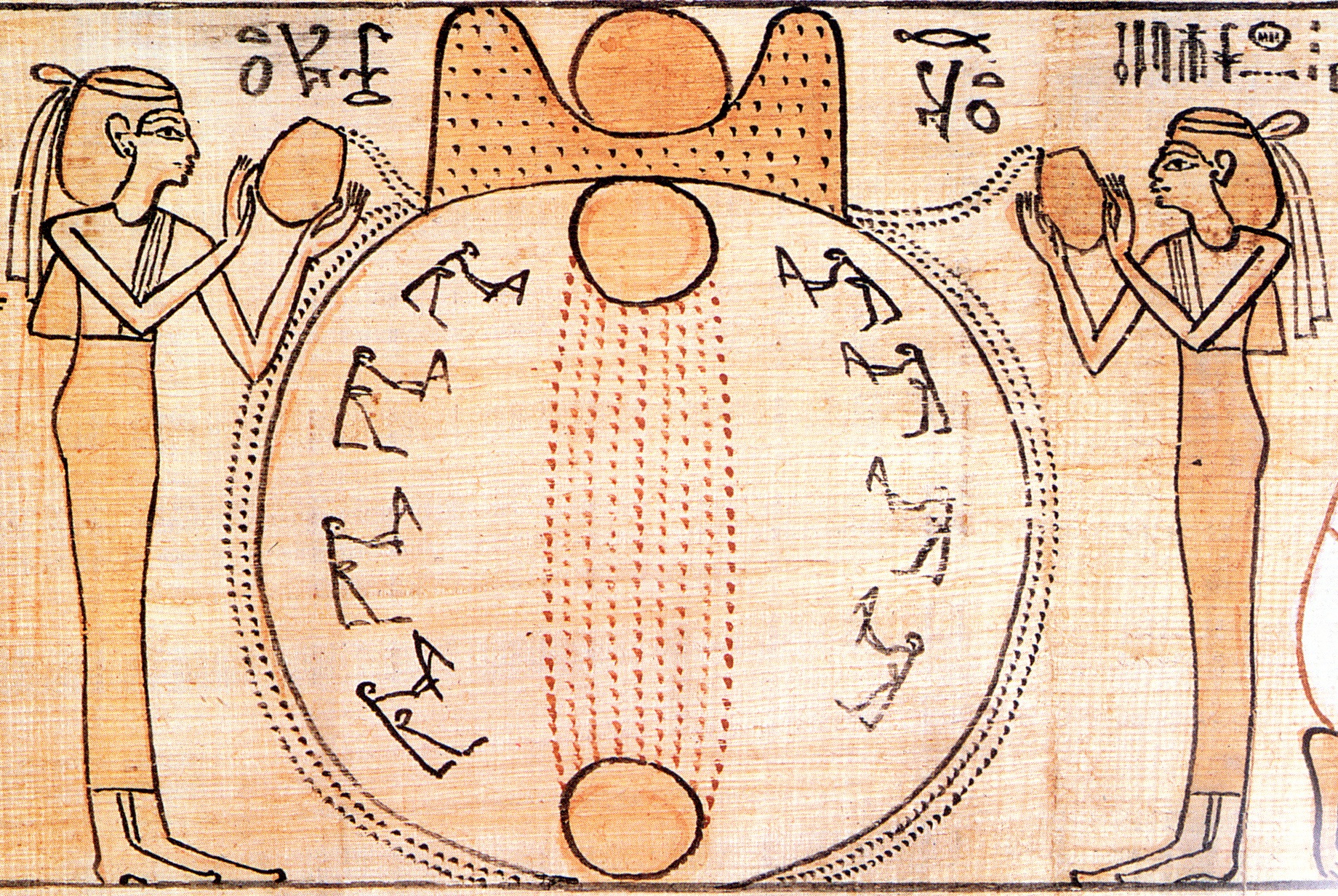

Sunrise at Creation: The sun rises over the circular mound of creation as goddesses pour out the primeval waters around it

Sunrise at Creation: The sun rises over the circular mound of creation as goddesses pour out the primeval waters around it

Scanned from the book Ancient Egypt, edited by David P. Silverman, p. 121; photograph from the Book of the Dead of Khensumose

Thales of Miletus, considered the first Greek philosophical sage (Melitus is in modern-day Turkey) was wealthy and may have traveled to Egypt and saw these creation myths on the walls of temples (where we found them also).

Thales (around 600 B.C.) brought them home and created a philosophy around them: everything on the Earth started as water. It's an astounding thing to say, because we don't observe this behavior in nature. You can find hints of it, when, say, you evaporate a glass of seawater to dryness, but nice pure rain water doesn't do this. But his theory of elements starts with water, from which all other matter is formed. The land, the sky, eventually fire.

Aristotle laid out his own thinking about matter and form which may shed some light on the ideas of Thales, in Metaphysics 983 b6 8–11, 17–21. (The passage contains words that were later adopted by science with quite different meanings.)

That from which is everything that exists and from which it first becomes and into which it is rendered at last, its substance remaining under it, but transforming in qualities, that they say is the element and principle of things that are. …For it is necessary that there be some nature (φύσις), either one or more than one, from which become the other things of the object being saved... Thales the founder of this type of philosophy says that it is water.

Wikipedia: Thales of Miletus

This marks the beginning of the Greek Philosopher, more interested in the thinking than in making their philosophy describe their observations. It's a trend that will last at least past 300 B.C. Thales worked in astronomy, hydraulics, geometry and the nature of God, but his ideas about water had the most influence.

The Miletus School of philosophers followed and expounded on what Thales taught. Water became a first "element" or "Principle" of matter.

Anaximander thought there were four elements, each primordial. They are recycled as the "waste" of mortality.

"Anaximander taught, then, that there was an eternal. The indestructible something out of which everything arises, and into which everything returns; a boundless stock from which the waste of existence is continually made good, “elements.”. That is only the natural development of the thought we have ascribed to Thales, and there can be no doubt that Anaximander at least formulated it distinctly. Indeed, we can still follow to some extent the reasoning which led him to do so. Thales had regarded water as the most likely thing to be that of which all others are forms; Anaximander appears to have asked how the primary substance could be one of these particular things. His argument seems to be preserved by Aristotle, who has the following passage in his discussion of the Infinite: "Further, there cannot be a single, simple body which is infinite, either, as some hold, one distinct from the elements, which they then derive from it, or without this qualification. For there are some who make this. (i.e. a body distinct from the elements). the infinite, and not air or water, in order that the other things may not be destroyed by their infinity. They are in opposition one to another. air is cold, water moist, and fire hot. and therefore, if any one of them were infinite, the rest would have ceased to be by this time. Accordingly they say that what is infinite is something other than the elements, and from it the elements arise.'—Aristotle Physics. F, 5 204 b 22 (Ritter and Preller (1898) Historia Philosophiae Graecae, section 16 b)."

Anaximenes settled back on air as the primordial element. “Just as our soul...being air holds us together, so pneuma and air encompass [and guard] the whole world.” (Vamvacas, Constantine J. (2009), "Anaximenes of Miletus (ca. 585–525 B.C.)", The Founders of Western Thought – the Presocratics, Springer Netherlands, pp. 45–51). The phrase "breath of life" comes from Anaximenes.

Minor Miletians selected earth or fire as the primordial element.

Empedocles later selected all four.

Empedocles established four ultimate elements which make all the structures in the world—fire, air, water, earth.[29][40] Empedocles called these four elements "roots", which he also identified with the mythical names of Zeus, Hera, Nestis, and Aidoneus[41] (e.g., "Now hear the fourfold roots of everything: enlivening Hera, Hades, shining Zeus. And Nestis, moistening mortal springs with tears").[42] Empedocles never used the term "element" (στοιχεῖον, stoicheion), which seems to have been first used by Plato.[43] According to the different proportions in which these four indestructible and unchangeable elements are combined with each other the difference of the structure is produced.[29] It is in the aggregation and segregation of elements thus arising, that Empedocles, like the atomists, found the real process which corresponds to what is popularly termed growth, increase or decrease. Nothing new comes or can come into being; the only change that can occur is a change in the juxtaposition of element with element.[29] This theory of the four elements became the standard dogma for the next two thousand years.

Wikipedia: Empedocles

And thus was the stage set for the disaster of alchemy. But the ideas needed hero, a believable hero. A hero of ideas so believed that no one would consider calling them wrong. These ideas needed Plato.

03 Plato

Plato inherited the four-element idea from Empedocles. About 360 B.C. he wrote Timaeus where the foundations of alchemy are set forth. These underpinnings take the form of two concepts: Being & Becoming, and Transmutation. Note that Plato was not an alchemist. He was a philosopher, but so pervasive are his ideas that later alchemists almost always style themselves as philosophers also. Sorry for the long quotations below.

Plato inherited the four-element idea from Empedocles. About 360 B.C. he wrote Timaeus where the foundations of alchemy are set forth. These underpinnings take the form of two concepts: Being & Becoming, and Transmutation. Note that Plato was not an alchemist. He was a philosopher, but so pervasive are his ideas that later alchemists almost always style themselves as philosophers also. Sorry for the long quotations below.

Being & Becoming. Plato, and his pupil Aristotle, are categorizers. Always organizing ideas and object in various categories. Foundationally are the two categories of Being and Becoming. Things that are being are perfect, have no change, are always right. Things which are becoming are imperfect, in the process of becoming more like God (as is the whole Earth), and thus are always changing and are not yet true. Into the Being category he places reason. Into the Becoming category he places opinion and observation.

First then, in my judgment, we must make a distinction and ask, What is that which always is and has no becoming, and what is that which is always becoming and never is? That which is apprehended by intelligence and reason is always in the same state, but that which is conceived by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason is always in a process of becoming and perishing and never really is. Now everything that becomes or is created must of necessity be created by some cause, for without a cause nothing can be created. The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect, but when he looks to the created only and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect. Was the heaven then or the world, whether called by this or by any other more appropriate name – assuming the name, I am asking a question which has to be asked at the beginning of an inquiry about anything – was the world, I say, always in existence and without beginning, or created, and had it a beginning? Created, I reply, being visible and tangible and having a body, and therefore sensible, and all sensible things are apprehended by opinion and sense, and are in a process of creation and created. Now that which is created must, as we affirm, of necessity be created by a cause. But the father and maker of all this universe is past finding out, and even if we found him, to tell of him to all men would be impossible. This question, however, we must ask about the world. Which of the patterns had the artificer in view when he made it – the pattern of the unchangeable or of that which is created? If the world be indeed fair and the artificer good, it is manifest that he must have looked to that which is eternal, but if what cannot be said without blasphemy is true, then to the created pattern. Everyone will see that he must have looked to the eternal, for the world is the fairest of creations and he is the best of causes. And having been created in this way, the world has been framed in the likeness of that which is apprehended by reason and mind and is unchangeable, and must therefore of necessity, if this is admitted, be a copy of something . . .

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961);

Here Plato is using reason and observation in the opposite sense we do today; for us observation is undeniable fact, and reason can take any fancy it likes. But for the alchemist who reads the Timaeus dialog, reason is paramount and observation is suspect. Aristotle will take this to new levels.

Plato expounds on the four-element theory of Empedocles by doing several things. First, he established via reason that the creator is good, perfect, and wants everything to be like He is. The world is not perfect, but it is changing to become so. Thus, the world is alive, like plants and animals are alive; he called it anima mundi, the "aliveness of the world".

TIMAEUS: Let me tell you then why the creator made this world of generation. He was good, and the good can never have any jealousy of anything. And being free from jealousy, he desired that all things should be as like himself as they could be. This is in the truest sense the origin of creation and of the world, as we shall do well in believing on the testimony of wise men. God desired that all things should be good and nothing bad, so far as this was attainable. Wherefore also finding the whole visible sphere not at rest, but moving in an irregular and disorderly fashion, out of disorder he brought order, considering that this was in every way better than the other. Now the deeds of the best could never be or have been other than the fairest, and the creator, reflecting on the things which are by nature visible, found that no unintelligent creature taken as a whole could ever be fairer than the intelligent taken as a whole, and again that intelligence could not be present in anything which was devoid of soul. For which reason, when he was framing the universe, he put intelligence in soul, and soul in body, that he might be the creator of a work which was by nature fairest and best. On this wise, using the language of probability, we may say that the world came into being – a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence by the providence of God.

This being supposed, let us proceed to the next stage. In the likeness of what animal did the creator make the world? It would be an unworthy thing to liken it to any nature which exists as a part only, for nothing can be beautiful which is like any imperfect thing. But let us suppose the world to be the very image of that whole of which all other animals both individually and in their tribes are portions. For the original of the universe contains in itself all intelligible beings, just as this world comprehends us and all other visible creatures. For the deity, intending to make this world like the fairest and most perfect of intelligible beings, framed one visible animal comprehending within itself all other animals of a kindred nature. Are we right in saying that there is one world, or that they are many and infinite? There must be one only if the created copy is to accord with the original. For that which includes all other intelligible creatures cannot have a second or companion; in that case there would be need of another living being which would include both, and of which they would be parts, and the likeness would be more truly said to resemble not them, but that other which included them. In order then that the world might be solitary, like the perfect animal, the creator made not two worlds or an infinite number of them, but there is and ever will be one only-begotten and created heaven. [27c–31b]

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961)

Secondly, Plato establishes that in the Creation, the world contains all the fire, air, water and earth that could exist, and that each of these contains differing properties that we observe. For example, earth always moves down toward the center of the spherical earth, and fire always moves up. Air and water behave similarly, but to a lesser extent.

Now the creation took up the whole of each of the four elements, for the creator compounded the world out of all the fire and all the water and all the air and all the earth, leaving no part of any of them nor any power of them outside. His intention was, in the first place, that the animal should be as far as possible a perfect whole and of perfect parts, secondly, that it should be one, leaving no remnants out of which another such world might be created, and also that it should be free from old age and unaffected by disease. Considering that if heat and cold and other powerful forces surround composite bodies and attack them from without, they decompose them before their time, and by bringing diseases and old age upon them make them waste away – for this cause and on these grounds he made the world one whole, having every part entire, and being therefore perfect and not liable to old age and disease. And he gave to the world the figure which was suitable and also natural. Now to the animal which was to comprehend all animals, that figure would be suitable which comprehends within itself all other figures. Wherefore he made the world in the form of a globe, round as from a lathe, having its extremes in every direction equidistant from the center, the most perfect and the most like itself of all figures, for he considered that the like is infinitely fairer than the unlike . . . Of design he was created thus – his own waste providing his own food, and all that he did or suffered taking place in and by himself. For the creator conceived that a being which was self-sufficient would be far more excellent than one which lacked anything, and, as he had no need to take anything or defend himself against anyone, the creator did not think it necessary to bestow upon him hands, nor had he any need of feet, nor of the whole apparatus of walking. But the movement suited to his spherical form was assigned to him, being of all the seven that which is most appropriate to mind and intelligence, and he was made to move in the same manner and on the same spot, within his own limits revolving in a circle. All the other six motions were taken away from him, and he was made not to partake of their deviations. And as this circular movement required no feet, the universe was created without legs and without feet.

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961)

Plato continues then to the transmutation of the elements by introducing the idea of prima materia, primeval matter, matter which has no properties. Yet. To explain the act of matter taking on properties, he first needs matter with a soul, matter which is in some sense alive.

Such was the whole plan of the eternal God about the god that was to be; he made it smooth and even, having a surface in every direction equidistant from the center, a body entire and perfect, and formed out of perfect bodies. And in the center he put the soul, which he diffused throughout the body, making it also to be the exterior environment of it, and he made the universe a circle moving in a circle, one and solitary, yet by reason of its excellence able to converse with itself, and needing no other friendship or acquaintance. Having these purposes in view he created the world a blessed god. Now God did not make the soul after the body, although we are speaking of them in this order, for when he put them together he would never have allowed that the elder should be ruled by the younger, but this is a random manner of speaking which we have, because somehow we ourselves too are very much under the dominion of chance. Whereas he made the soul in origin and excellence prior to and older than the body, to be the ruler and mistress, of whom the body was to be the subject. [32c–34c] Now when the creator had framed the soul according to his will, he formed within her the corporeal universe, and brought the two together and united them center to center. The soul, interfused everywhere from the center to the circumference of heaven, of which also she is the external envelopment, herself turning in herself, began a divine beginning of never-ceasing and rational life enduring throughout all things. [36d–e]

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961)

Now he is ready to introduce transmutation, the shifting of the properties of matter, by the matter itself, to move it toward perfection.

Thus far in what we have been saying, with small exceptions, the works of intelligence have been set forth, and now we must place by the side of them in our discourse the things which come into being through necessity – for the creation of this world is the combined work of necessity and mind. Mind, the ruling power, persuaded necessity to bring the greater part of created things to perfection, and thus and after this manner in the beginning, through necessity made subject to reason, this universe was created. But if a person will truly tell of the way in which the work was accomplished, he must include the variable cause as well, and explain its influence. Wherefore, we must return again and find another suitable beginning – as about the former matters, so also about these. To which end we must consider the nature of fire and water and air and earth, such as they were prior to the creation of the heaven, and what was happening to them in this previous state, for no one has as yet explained the manner of their generation, but we speak of fire and the rest of them, as though men knew their natures, and we maintain them to be the first principles and letters or elements of the whole, when they cannot reasonably be compared by a man of any sense even to syllables or first compounds . . .

In the first place, we see that what we just now called water, by condensation, I suppose, becomes stone and earth, and this same element, when melted and dispersed, passes into vapor and air. Air, again, when inflamed, becomes fire, and, again, fire, when condensed and extinguished, passes once more into the form of air, and once more, air, when collected and condensed, produces cloud and mist – and from these, when still more compressed, comes flowing water, and from water comes earth and stones once more – and thus generation appears to be transmitted from one to the other in a circle. Thus, then, as the several elements never present themselves in the same form, how can anyone have the assurance to assert positively that any of them, whatever it may be, is one thing rather than another? No one can . . .

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961)

And there it is. Matter, having a soul, can direct the properties it has to become more perfect. It can transform by altering those properties. Plato gives us examples, centered around gold.

Let me make another attempt to explain my meaning more clearly. Suppose a person to make all kinds of figures of gold and to be always remodeling each form into all the rest; somebody points to one of them and asks what it is. By far the safest and truest answer is, ‘That is gold,’ and not to call the triangle or any other figures which are formed in the gold ‘these,’ as though they had existence, since they are in process of change while he is making the assertion, but if the questioner be willing to take the safe and indefinite expression, ‘such,’ we should be satisfied. And the same argument applies to the universal nature which receives all bodies – that must be always called the same, for, inasmuch as she always receives all things, she never departs at all from her own nature and never, in any way or at any time, assumes a form like that of any of the things which enter into her; she is the natural recipient of all impressions, and is stirred and informed by them, and appears different from time to time by reason of them . . . Wherefore the mother and receptacle of all created and visible and in any way sensible things is not to be termed earth or air or fire or water, or any of their compounds, or any of the elements from which these are derived, but is an invisible and formless being which receives all things and in some mysterious way partakes of the intelligible, and is most incomprehensible. In saying this we shall not be far wrong; as far, however, as we can attain to a knowledge of her from the previous considerations, we may truly say that fire is that part of her nature which from time to time is inflamed, and water that which is moistened, and that the mother substance becomes earth and air, in so far as she receives the impressions of them. [47e–51b]

Of all the kinds termed fusile [by which he means metals], that which is the densest and is formed out of the finest and most uniform parts is that most precious possession called gold, which is hardened by filtration through rock; this is unique in kind, and has both a glittering and a yellow color. A shoot of gold, which is so dense as to be very hard, and takes a black color, is termed adamant. There is also another kind which has parts nearly like gold, and of which there are several species; it is denser than gold, and it contains a small and fine portion of earth and is therefore harder, yet also lighter because of the great interstices which it has within itself, and this substance, which is one of the bright and denser kinds of water, when solidified is called copper. [59b–c]

From the translation of the Timaeus by Benjamin Jowett, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollingen Series LXXI (New York: Pantheon Books, 1961)

Aristotle will take these ideas, and run with them.

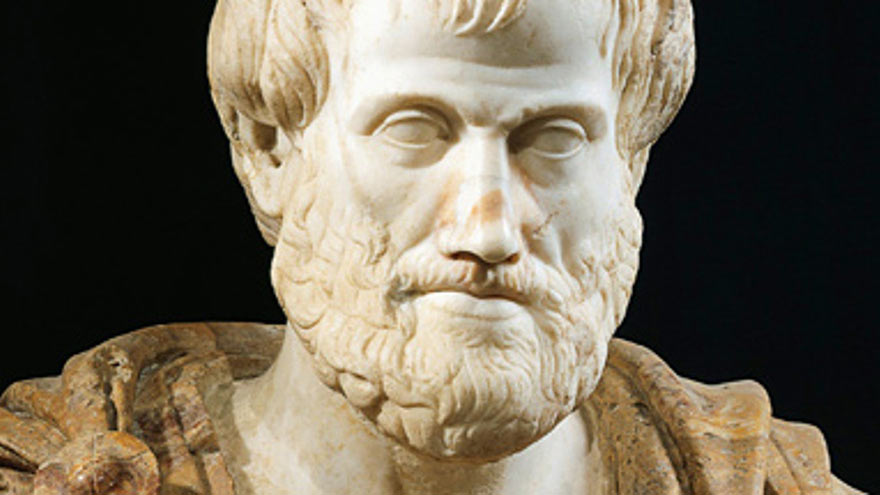

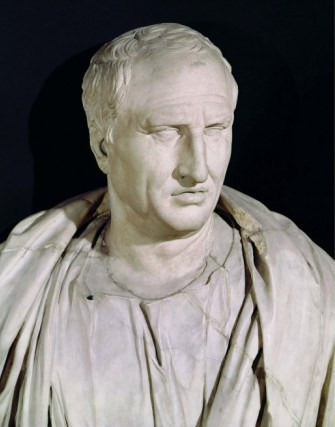

04 Aristotle

Aristotle, the pupil of Plato, is considered one of the best minds the world has every produced. I'm afraid is just wasn't so, but ask anyone before 1600 who was the smartest man to ever live, and Aristotle would be the only answer you heard. He was seriously challenged by only two men, Diogenes who attended Plato and Aristotle's talks and made fun of them, and in 1536 by Peter Rami (Petrus Ramus in the Latinized form) in his Master's thesis Quaecumque ab Aristotele dicta essent, commentitia esse (Everything that Aristotle has said is false).

Aristotle was a good writer. I think that's why he's famous. His ideas are to our ears silly, but they were believable if you didn't look at nature so closely that you saw the flaws in Aristotle's statements of now Nature operates.

Around 300 B.C Aristotle wrote Meteorology, where the ideas of alchemy are presented. Again, Aristotle is not an alchemist, but alchemy would be constructed on his ideas.

We have already laid down that there is one principle which makes up the nature of the bodies that move in a circle, and besides this four bodies owing their existence to the four principles [elements], the motion of these latter bodies being of two kinds: either from the centre or to the centre. These four bodies are fire, air, water, earth. Fire occupies the highest place among them all, earth the lowest, and two elements correspond to these in their relation to one another, air being nearest to fire, water to earth. The whole world surrounding the earth [water, air, fire, cosmos], then, the affections of which are our subject, is made up of these bodies. This world necessarily has a certain continuity with the upper motions [the movements of the planets are influencing us]; consequently all its power is derived from them. (For the originating principle of all motion must be deemed the first cause. Besides, that element is eternal and its motion has no limit in space, but is always complete; whereas all these other bodies have separate regions which limit one another.) So we must treat fire and earth and the elements like them as the material causes of the events in this world (meaning by material what is subject and is affected), but must assign causality in the sense of the originating principle of motion to the power of the eternally moving bodies . . . Fire, air, water, earth, we assert, come-to-be from one another, and each of them exists potentially in each, as all things do that can be resolved into a common and ultimate substrate. [Bk. 1, 339a 11–339b 2]

So at the centre and round it [the earth-centred world] we get earth and water, the heaviest and coldest elements, by themselves; round them and contiguous with them, air and what we commonly call fire. It is not really fire, for fire is an excess of heat and a sort of ebullition; but in reality, of what we call air, the part surrounding the earth is moist and warm, because it contains both vapour and a dry exhalation from the earth. But the next part, above that, is warm and dry. For vapour is naturally moist and cold, exhalation warm and dry; and vapour is potentially like water, exhalation potentially like fire. [Bk. 1, 340b 19–28]

From the translation of the Meteorology by E. W. Webster, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, Revised Oxford Translation, ed. Jonathan Barnes, Bollingen Series 71.2, vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984)

We have a few ideas here. The cosmos, circling as it does by way of it's natural motion to go in circles, is influencing everything below, in our sublunary sphere. We also have the formation of metals in the two vapors that exist below ground, the moist vapors and the dry ones. Keep in mind that Aristotle was from Greece, a geologically active area, and would have been familiar with volcanos.

| Element | Hot/Cold | Wet/Dry | Motion | Modern state of matter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | Cold | Dry | Down | Solid |

| Water | Cold | Wet | Down | Liquid |

| Air | Hot | Wet | Up | Gas |

| Fire | Hot | Dry | Up | Plasma |

| Aether | (divine substance) |

— | Circular (in heavens) |

— |

He continues with an important idea, that by exposing a lesser metal, like copper, to wet or dry vapors, the nature of the metal is changed; it becomes a different metal. Aristotle has adopted the Platonic transmutation, and has defined how it is done: by altering the metal's properties.

We recognize two kinds of exhalation, one moist, the other dry. The former is called vapour: for the other there is no general name but we must call it a sort of smoke, applying to the whole of it a word that is proper to one of its forms. The moist cannot exist without the dry nor the dry without the moist: whenever we speak of either we mean that it predominates. Now when the sun in its circular course approaches, it draws up by its heat the moist evaporation: when it recedes the cold makes the vapour that had been raised condense back into water which falls and is distributed over the earth. (This explains why there is more rain in winter and more by night than by day: though the fact is not recognized because rain by night is more apt to escape observation than by day.) But there is a great quantity of fire and heat in the earth, and the sun not only draws up the moisture that lies on the surface of it, but warms and dries the earth itself. Consequently, since there are two kinds of exhalation, as we have said, one like vapour, the other like smoke, both of them are necessarily generated. That in which moisture predominates is the source of rain, as we explained before, while the dry one is the source and substance of all winds. [Bk. 2, 359b 29–360a 13]

Some account has now been given of the effects of the exhalation above the surface of the earth; we must go on to describe its operations below, when it is shut up in the parts of the earth.

Its own twofold nature gives rise here to two varieties of bodies, just as it does in the upper region. We maintain that there are two exhalations, one vaporous the other smoky, and there correspond two kinds of bodies that originate in the earth, things quarried and things mined. The heat of the dry exhalation is the cause of all things quarried. Such are the kinds of stones that cannot be melted, and realgar, and ochre, and ruddle, and sulphur, and the other things of that kind, most things quarried being either coloured lye or, like cinnabar, a stone compounded of it. The vaporous exhalation is the cause of all things mined – things which are either fusible or malleable such as iron, copper, gold. All these originate from the imprisonment of the vaporous exhalation in the earth, and especially in stones. Their dryness compresses it, and it congeals just as dew or hoar-frost does when it has been separated off, though in the present case the metals are generated before that separation occurs. Hence, they are water in a sense, and in a sense not. Their matter was that which might have become water, but it can no longer do so; nor are they, like savours, due to a qualitative change in actual water. Copper and gold are not formed like that, but in every case the evaporation congealed before water was formed. Hence, they all (except gold) are affected by fire, and they possess an admixture of earth; for they still contain the dry exhalation.

This is the general theory of all these bodies, but we must take up each kind of them and discuss it separately. [Bk. 3, 378a 14–378b 6]

We have explained that the causes of the elements are four, and that their combinations determine the number of the elements to be four.

Two of the causes, the hot and the cold, are active; two, the dry and the moist, passive. We can satisfy ourselves of this by looking at instances. In every case heat and cold determine, conjoin, and change things of the same kind and things of different kinds, moistening, drying, hardening, and softening them. Things dry and moist, on the other hand, both in isolation and when present together in the same body are the subjects of that determination and of the other affections enumerated. The account we give when we define their natures shows this too. Hot and cold we describe as active, for combining is a sort of activity; moist and dry are passive, for it is in virtue of its being acted upon in a certain way that a thing is said to be easy to determine or difficult to determine. So it is clear that some are active and some passive. [Bk. 4, 378b 10–25]

We must now describe the next kinds of processes which the qualities already mentioned set up in actually existing natural objects as matter.

Of these concoction is due to heat; its species are ripening, boiling, broiling . . . Concoction is a process in which the natural and proper heat of an object perfects the corresponding passive qualities, which are the proper matter of any given object. For when concoction has taken place we say that a thing has been perfected and has come to be itself. It is the proper heat of a thing that sets up this perfecting, though external influences may contribute in some degree to its fulfilment . . . In some cases of concoction the end of the process is the nature of the thing – nature, that is, in the sense of the form and essence. [Bk. 4, 379b 10–26]

Homogeneous bodies differ to touch by these affections and differences, as we have said. They also differ in respect of their smell, taste, and colour.

By homogeneous bodies I mean, for instance, the stuffs that are mined – gold, copper, silver, tin, iron, stone, and everything else of this kind and the bodies that are extracted from them . . . [Bk. 4, 388a 10–15]

From the translation of the Meteorology by E. W. Webster, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, Revised Oxford Translation, ed. Jonathan Barnes, Bollingen Series 71.2, vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984)

Sorry this is so long, but so was Aristotle. He has redefined transmutation by making it all about the properties. Instead of earth, air, water and fire, he has hot/cold and dry/wet. Start with any matter, and subject it to one of these four properties, and by adding that property to the matter, new matter will result. This is the core philosophy of alchemy. And by using gold as his example, he set the stage for alchemy centered on the production of gold.

What's needed now is for these ideas to be spread abroad.

Thus enters Aristotle's pupil, Alexander the Great.

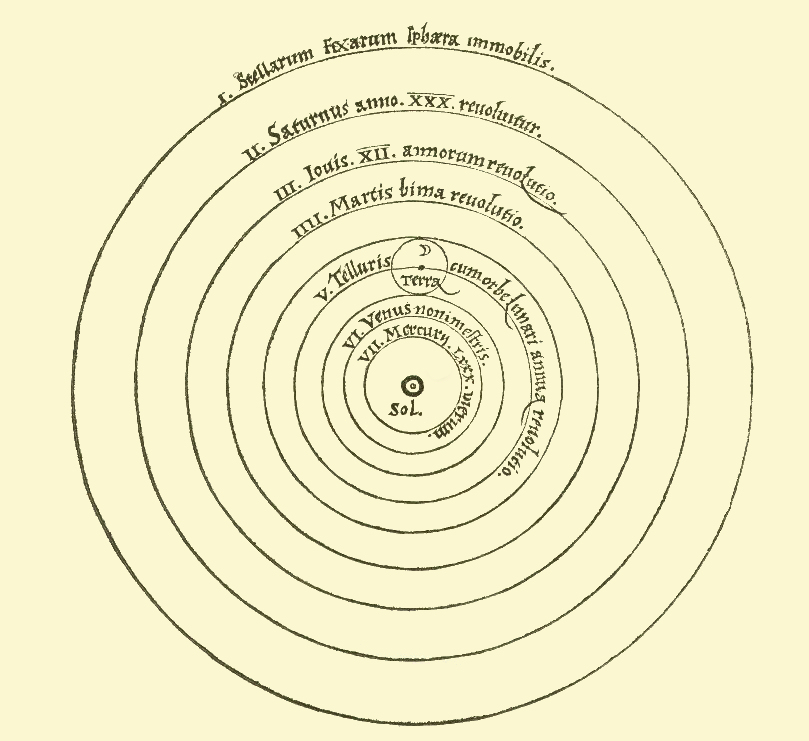

The Aristotelean Cosmos, as Ptolemy rendered it:

05 Diogenes: Challenging Philosophy

Diogenes tried hard to challenge the ideas underpinning alchemy. He was a troll, attending lectures and making fun of what was said or otherwise distracting from the solemnity of the moment. He wore only a blanket, slept where he wanted, tried his best to live a completely honest life, though not a comfortable one. He tried to live up to his own high ideals.

You can search out and read the many stories of the life of Diogenes, but his manner platform.

Diogenes couldn't do it. But he was our first cynic. Today cynicism is one of the foundations of the scientific method: don't believe anything which isn't multiple-times proven.

06 Alexander: Spreading Ideas

Alexander III, son of Philip of Macedon, was at the age of 16 a pupil of Aristotle. As his pupil he would have heard of Plato. Philip was obsessed with conquering Persia, current-day Iran/Iraq, as a consequence of Persia conquering all the known world around 540 B.C. and into Greece around 480 B.C. (and in the process, as Cyrus passed through Babylon, freed the Hebrews taken 60 years earlier). Alexander fulfilled that obsession by taking it all back. In 336 B.C. he took Philips army across Anatolia (Turkey, 333 B.C.), the Levant (Syria and Israel, 332 B.C.), Egypt (331 B.C.), Persia (Iran/Iraq, 330 B.C.), into the northeast provinces (Afganistan/Pakistan, 329 B.C.) and into Punjab (western India and Tibet, 328 B.C.).

His army moved fast, and picked up many many warriors along the way. He did this by not being a cruel tyrant, but by opening trade in every land he conquered. His goal was not to tax, but to trade with everyone. Calm the land and open the trade routes. Teach everyone a simplified Greek (Koine Greek, common Greek), and let them govern themselves. Part of this was (probably, for this I have no proof) indoctrination into the Greek culture by bringing books with them, books like Aristotle's Meteorology and Plato's Timaeus. Books the Greeks told them to read so they could understand them. And read them they did. When alchemy was developed, it seem to spring from all parts of the old world:

It worked well. The conquered people never rebelled, and hundreds of years later, Hellenism (as we call it) was still intact.

Towns were founded to help with the trade routes. Alexandria, in Egypt, as a trade port. In fact, almost every area conquered had a new Alexandria. All were founded as classical Greek cities.

But revolt did come, from his generals. Alexander wasn't done. He wanted to go as far as China, but the troops were done. In the end Alexander settled down in Babylon, and died in Nebuchadnezzar's palace in 323 B.C., probably from foul play. The empire was willed to four generals: Ptolemy got Egypt, Seleucid got Mesopotamia and Central Asia, Attalid got Anatolia (Turkey) and the Levant (Syria/Israel), and Antigonid got Macedonia, the Greek homeland. Each ruled by his own standards.

Ptolemy's kingdom lasted the longest, and was the most generous. He funded huge libraries over his little empire, and Alexandria became the world center of learning. By decree any book brought into Alexandria was allowed to be copied for the library, but typically the copy was returned to the owner; the original stayed with the library. Books at the great library of Alexandria were copied for the other libraries around the Mediterranean, and famous men began to be identified by the city housing the library where they studied.

But it was at Alexandria that the most ideas met. And fused. And grew.

07 Astrology and Magic: Status Quo

Alchemy, astrology and Magic always seem to go together. They were combined in the early renaissance as a deliberate act, but early on they were informally combined as they all fit the same cosmology and religion.

We have seen a hint of this in Plato, where he had the Gods living far outside the sphere of the earth, and by the rotation of the planetary spheres have some influence over the earth. Aristotle made this a central aspect of his cosmology. But the origins are earlier.

From Persian Zoroastrianism (600 B.C., note the date relative to the conquest of the old world by the Persians) came the love of wisdom and the idea that all the world seeks to be like God. As these ideas were carried to Greece by Heraclitus (500 B.C.) he brought with it some mathematics which inspired Pythagoras, the eastern forms of astrology, and the practice of natural magic brought to Greece by Ostanes.

Astrology was practiced by everybody by about 2000 B.C. The astrologers controlled the calendar, and most religions incorporated astrology as the means of finding out which gods were influencing you right now. Egyptian religion went as far as to enumerate the "siderial gods" 36 in number, who rule each 40-minute block of each day.

Magic was not the black magic we play with on Halloween, it was the natural magic of using herbs to heal. It was a forerunner of medicinal alchemy and medicine. It required a vast understanding of the plants and how to prepare them so they would heal.

As these arts were practiced, the astrologer would calculate which planets were in the sky at your birth. Since you came from heaven, your soul needed to pass through each planetary sphere, picking up the vice associated with each one (pride, envy, wrath, sloth, greed, gluttony, lust) each associated with a particular body in the cosmos. As these influence us, some have greater influences than others. That imparts our character.

These vice-like aspects can be overcome. It requires that the astrologer find the "antidote" by finding the planets, stars, plants, shapes, objects that will undo our vices, then at the correct time of year, at the feet of the correct statue of deity, imbue a talisman that can help undo our vices. Potion making worked the same way.

An astrologer would need to be a magician and later an alchemist to perform astrology. Alchemists relied on astrologers to get the timing right, and later some would become makers of medicines.

08 Democritus: What Might Have Been

Democritus around 350 B.C. had a nice theory of atoms. He said any bit of matter can be divided up to a point. When the particles are small enough, they can be divided no further. He called these "atoms."

Plato hated him, Aristotle ignored him, and he taught Pythagoras.

He came to his atomic theory not how Dalton came to his in the very early 1800's. Democritus thought atoms were unique in shape, and when they stacked together there was empty space between them (an idea both Plato and Aristotle rejected utterly in their philosophies).

Lucretius, describing atomism in his De rerum natura, gives very clear and compelling empirical arguments for the original atomist theory. He observes that any material is subject to irreversible decay. Through time, even hard rocks are slowly worn down by drops of water. Things have the tendency to get mixed up: Mix water with soil and mud will result, seldom disintegrating by itself. Wood decays. However, there are mechanisms in nature and technology to recreate "pure" materials like water, air, and metals. The seed of an oak will grow out into an oak tree, made of similar wood as historical oak trees, the wood of which has already decayed. The conclusion is that many properties of materials must derive from something inside, that will itself never decay, something that stores for eternity the same inherent, indivisible properties. The basic question is: Why has everything in the world not yet decayed, and how can exactly some of the same materials, plants, and animals be recreated again and again? One obvious solution to explain how indivisible properties can be conveyed in a way not easily visible to human senses, is to hypothesize the existence of "atoms". These classical "atoms" are nearer to humans' modern concept of "molecule" than to the atoms of modern science. The other central point of classical atomism is that there must be considerable open space between these "atoms": the void. Lucretius gives reasonable arguments that the void is absolutely necessary to explain how gases and liquids can flow and change shape, while metals can be molded without their basic material properties changing.

Wikipedia - Democritus

The idea of atoms is fundamental to our understanding matter and everything to do with matter. Once atoms are understood it merely forty years before chemistry and technology are in full swing.

So where would we be if Democritus was believed instead of Plato and Aristotle?

Richard Feynmann, renowned Nobel physicist, said this:

If, through some cataclysm, all scientific knowledge were to be lost, and only one sentence could be passed on to the following generations, what single statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? All things are made of atoms -- little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another. In that one sentence, you will see, there is an enormous amount of information about the world, if just a little imagination and thinking are applied.

James Gleick, Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman

09 Pseudo-Democritus

The first writings we have on Alchemy are recipes. A little obscure philosophy, mostly instructions. This is dated first of second centuries A.D. but it could be as late as 400 A.D. Martelli puts this at 60 A.D. [Martelli, Matteo, The Four Books of Pseudo-Democritus (Manley Publishing: Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry, 2013)]

It portends to be the Greek Democritus speaking, but we know it isn't. The author is Greek. There is a blend of mysticism ( aka magic) and philosophy here that puts it almost certainly in Alexandria. But already alchemy is developed much further than we generally think it would be. It is this early development which fascinates me, and is my only real proof that the ideas in the Timaeus and the Meteorology were widely spread through out the Mediterranean area well before 100 A.D. Only familiarity with those two books would make alchemy easy to adopt. It's my guess that these books were spread by Alexander's army or the traders who followed.

The following text is a nearly complete version of the translation by Robert B. Steele that appeared in Chemical News, 61 (1890): 88–125; a number of Steele’s notes have been incorporated in the annotations. Steel is convinced that this is very early first century. I'm not convinced. Steele's comments are in [square brackets,] mine are in {curly braces.}

FRAGMENT OF ANCIENT INTRODUCTION

“Nature rejoices with Nature; Nature conquers Nature; Nature restrains Nature.” We (his disciples) greatly wondered at how briefly he had bound up the whole science. I come into Egypt, bearing the treatises of nature, that thou mayest cast off confused and superfluous matter.

1. Copper is Whitened with Mercury-Amalgam or Arsenic, and is then Coloured Golden by Electrum or Powdered Gold. Taking mercury, thrust it into the body of magnesia,[Any white body, steatite or soapstone. In later alchemical writing, magnesia has a broad range of meanings, including the quintessence or an ingredient of the philosopher’s stone.] or into the body of Italian antimony, or of unfired sulphur, or of silver spume,[Argentiferous litharge] or of quick lime, or to alum from Melos, or to arsenic, or as thou knowest, and throw in white earth of Venus, and thou shalt have clear Venus; then throw in yellow Luna,[Venus and Luna stand for copper and silver, respectively] and thou shalt have gold, and it will be chrysocoral[“gold solder” or chrysocolla, a name given to a specific mineral or minerals in ancient times] reduced into a body. Yellow arsenic also makes the same, and prepared sandarach,[red arsenic sulphide, or realgar] and well bruised cinnabar,{mercury sulfide, very easy to smelt} but quicksilver {mercury} alone makes brass shining; for nature conquers nature.

2. Sulphide of Silver is Treated with Sulphides of Lead or Antimony, and the Resulting Alloy is Coloured Golden. Treat silver marcasite, which is also called siderites, and do what is usual that it may be melted. It melts with yellow or white litharge, or in Italian antimony, and cleanse it with lead (not simply, say I, lest thou err, but with that from Scissile,[alum schist from Sicily] and our black litharge), or as thou knowest; and heat, and throw it made yellow to the material, and it becomes coloured; for nature rejoices with nature.

3. Copper Pyrites is Roasted and Treated with Salt and Alloyed with Silver or Gold to Form Gold-Coloured Alloys. Treat pyrites till it becomes incombustible, casting off darkness, but treat with brine, or fresh urine, or sea water, or oxymel, or as thou knowest, until it becomes as an incombustible shaving of gold; and as it becomes so, mix with it unfired sulphur, or yellow alum, or Attic ochre, or what thou knowest, and add to luna for sol, and to sol for auriconchylium;[sol represents gold; auriconchylium is gold in powder, coquille d’or] for nature conquers nature.

4. Claudian Metal is Rendered Yellow by Sulphur or Arsenic, and Alloyed on Gold or Silver. Taking claudianum,[a metal, named from its manufacturer. An alloy of tin and lead, with copper, zinc, &c.] thou shalt make a marble, as of custom, until it becomes yellow. Thou shalt not render the stone yellow, I say, but that which is useful of the stone. Thou shalt yellow it with alum burnt with sulphur, or with arsenic, or sandarach, or lime, or that thou knowest, and if thou apply it to luna thou makest sol,[gold] but if to sol thou makest auriconchylium; for victorious nature restrains nature.

5. Silver or Bronze are Treated with an Amalgam of Iron to Produce Gold or Electrum. Make cinnabar white by oil, or vinegar, or honey, or brine, or alum, then yellow by misy, or sory, or chalcanth,[misy: a mixture of iron and copper sulphate; sory: basic sulphate of iron; chalcanth: copperas or ferrous sulphate] or live sulphur, or that thou knowest, and add to luna and it will be sol if thou colourest golden, or to bronze for electrum. Nature rejoices with nature.

6. A Yellow Golden Varnish for Metals. Whiten, I say, copper, cadmia, or zonytes, as of custom, afterwards make it yellow. But you will yellow it with the bile of a calf, or terebinth,[the tree that serves as the source of turpentine or – most likely in this context – the resin itself] or castor oil, or radish oil, or yolks of eggs, which can render it yellow, and add to luna, for it will be gold for gold; for nature conquers nature.

7. The Treatment of Silver by Superficial Sulphidation to Render it Gold Coloured. Treat androdamas[arsenical pyrites; from its silvery lustre used with silver] with bitter wine, or sea water, or acid brine, which things can attack its nature, melt with Chalcidonian antimony, and treat it again with sea water, or brine, or acid brine; wash until the blackness of the antimony goes away, heat or roast it until it begins to grow yellow, and thou shalt treat with untouched divine water, and lay it on silver, and when thou addest live sulphur thou makest chrysosomium into golden liquid; for nature conquers nature. This is the stone called chrysites.[a mixture of silver and lead, which becomes yellow on heating]

8. An Alloy of Copper and Lead is Formed, which is turned Yellow. Taking white earth from ceruse, I say, or from the scoriæ of silver, or of Italian antimony, or of magnesia, or even of white litharge, whiten it with sea water, or acid brine, or with water from the air under the dew, I say, and the sun, that it, when dissolved, may become white as ceruse. Heat then this in the furnace, and add to it the flowers of copper,[small black scales of oxide of copper, which separate on cooling] or scraped rust of copper, worked up by art, I say, or burnt bronze sufficiently corroded, or chalcites, or cyanum;[chalcites is copper pyrites; cyanum is blue carbonate of copper or Azurite] then it becomes compact and solid, but it becomes so easily. This is molybdochalium.[an alloy of copper and lead] Test it therefore, whether it has cast off its blackness, but if not, blame not the bronze, but rather thyself, since thou hast not conducted the operation rightly; therefore thou shalt brighten it, and dissolve it, and add what is necessary to yellow it, and roast till it begins to grow yellow, and throw it into all bodies; for bronze colours every body where it is shining and yellow; for nature conquers nature.